Dateline: 6.25.12

From Mako Shark show car to production Corvette – a little too quickly.

In retrospect, it’s amazing that the C3 Corvette wasn’t called the “C2.5 Corvette.” After all, the frame, suspension, chassis, and running gear was straight off the C2 Sting Ray. It all goes to show how important looks can be. Of course, today, we’re all used to the “shark” style, but in September ‘67 when the ‘68 cars made their grand debut, it was WOWZERS for Chevrolet! To really appreciate how advanced and completely original the Mako Shark-inspired ‘68 Corvette was, go back an look at what Detroit was offering back then. Yes, there are a dozen of so genuinely classic cars from the late ‘60s, but the ‘68 Corvette was even more original than the ‘63 Sting Ray. The ‘68 – ‘82 Corvettes were so iconic, they are forever branded the “Shark” Corvettes.

In retrospect, it’s amazing that the C3 Corvette wasn’t called the “C2.5 Corvette.” After all, the frame, suspension, chassis, and running gear was straight off the C2 Sting Ray. It all goes to show how important looks can be. Of course, today, we’re all used to the “shark” style, but in September ‘67 when the ‘68 cars made their grand debut, it was WOWZERS for Chevrolet! To really appreciate how advanced and completely original the Mako Shark-inspired ‘68 Corvette was, go back an look at what Detroit was offering back then. Yes, there are a dozen of so genuinely classic cars from the late ‘60s, but the ‘68 Corvette was even more original than the ‘63 Sting Ray. The ‘68 – ‘82 Corvettes were so iconic, they are forever branded the “Shark” Corvettes.

Since we’re rolling into the C6’s final year and looking forward to the new 7th generation Vette, the next several installments of my VETTE Magazine monthly column looks back at the “first” of each generation Corvette. So, let’s go back to the first of the Shark Corvettes! – Scott

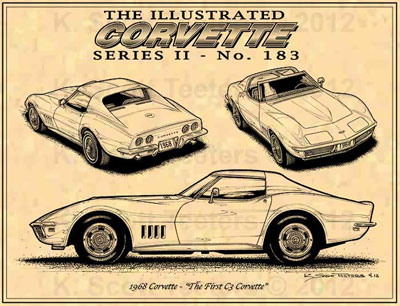

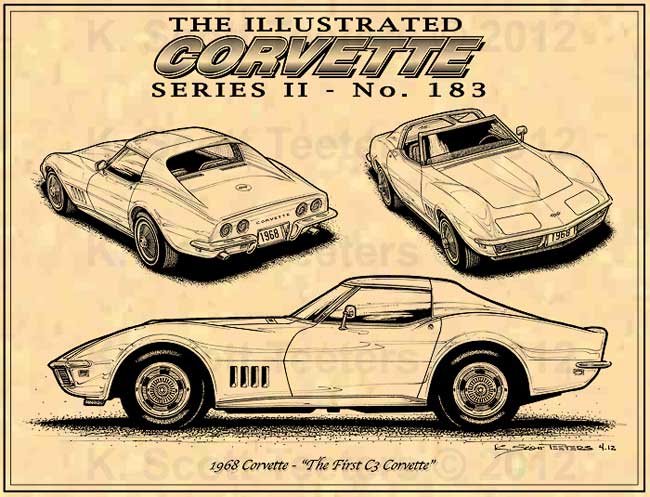

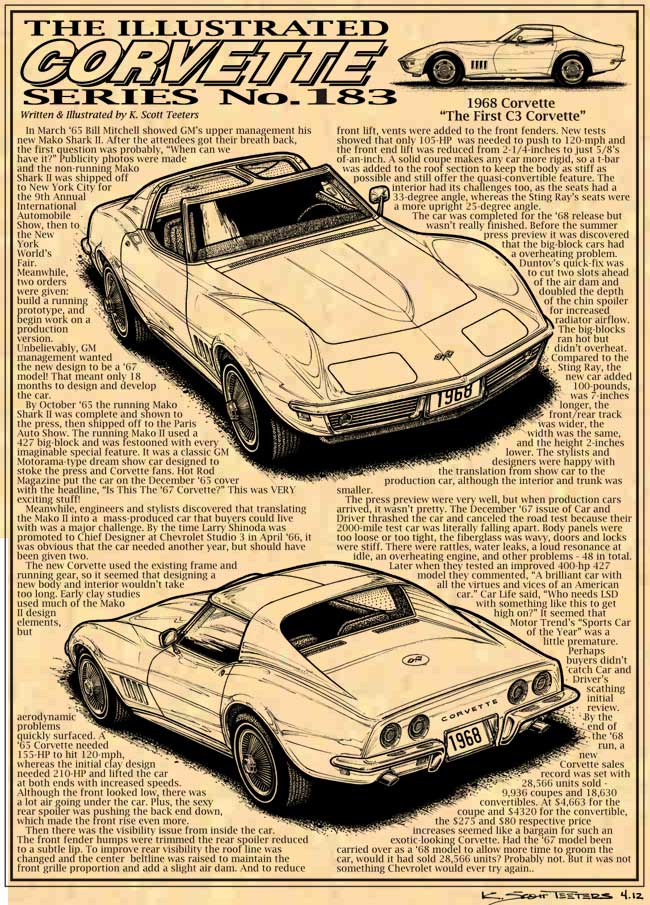

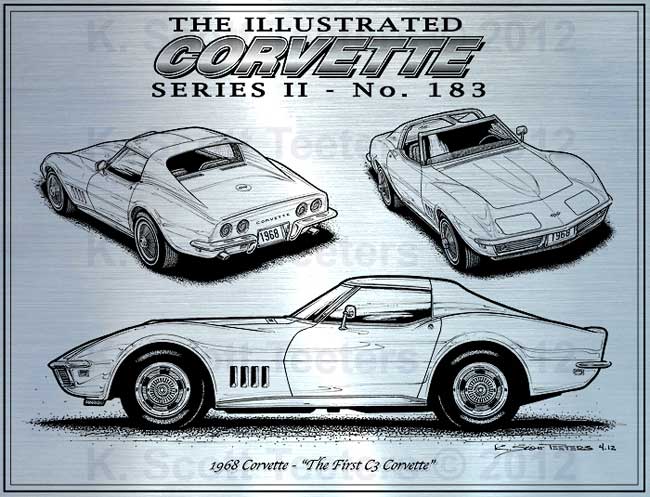

Illustrated Corvette Series No. 183: 1968 Corvette – “The First C3 Corvette”

In March ‘65 Bill Mitchell showed GM’s upper management his new Mako Shark II. After the attendees got their breath back, the first question was probably, “When can we have it?” Publicity photos were made and the non-running Mako Shark II was shipped off to New York City for the 9th Annual International Automobile Show, then to the New York World’s Fair. Meanwhile, two orders were given: build a running prototype, and begin work on a production version. Unbelievably, GM management wanted the new design to be a ‘67 model! That meant only 18 months to design and develop the car.

By October ‘65 the running Mako Shark II was complete and shown to the press, then shipped off to the Paris Auto Show. The running Mako II used a 427 big-block and was festooned with every imaginable special feature. It was a classic GM Motorama-type dream show car designed to stoke the press and Corvette fans. Hot Rod Magazine put the car on the December ‘65 cover with the headline, “Is This The ‘67 Corvette?” This was VERY exciting stuff!

By October ‘65 the running Mako Shark II was complete and shown to the press, then shipped off to the Paris Auto Show. The running Mako II used a 427 big-block and was festooned with every imaginable special feature. It was a classic GM Motorama-type dream show car designed to stoke the press and Corvette fans. Hot Rod Magazine put the car on the December ‘65 cover with the headline, “Is This The ‘67 Corvette?” This was VERY exciting stuff!

Meanwhile, engineers and stylists discovered that translating the Mako II into a mass-produced car that buyers could live with was a major challenge. By the time Larry Shinoda was promoted to Chief Designer at Chevrolet Studio 3 in April ‘66, it was obvious that the car needed another year, but should have been given two.

The new Corvette used the existing frame and running gear, so it seemed that designing a new body and interior wouldn’t take too long. Early clay studies used much of the Mako II design elements, but aerodynamic problems quickly surfaced. A ‘65 Corvette needed 155-HP to hit 120-mph, whereas the initial clay design needed 210-HP and lifted the car at both ends with increased speeds. Although the front looked low, there was a lot air going under the car. Plus, the sexy rear spoiler was pushing the back end down, which made the front rise even more.

Then there was the visibility issue from inside the car. The front fender humps were trimmed the rear spoiler reduced to a subtle lip. To improve rear visibility the roof line was changed and the center beltline was raised to maintain the front grille proportion and add a slight air dam. And to reduce front lift, vents were added to the front fenders. New tests showed that only 105-HP was needed to push to 120-mph and the front end lift was reduced from 2-1/4-inches to just 5/8’s of-an-inch. A solid coupe makes any car more rigid, so a t-bar was added to the roof section to keep the body as stiff as possible and still offer the quasi-convertible feature. The interior had its challenges too, as the seats had a 33-degree angle, whereas the Sting Ray’s seats were a more upright 25-degree angle.

The car was completed for the ‘68 release but wasn’t really finished. Before the summer press preview it was discovered that the big-block cars had a overheating problem. Duntov’s quick-fix was to cut two slots ahead of the air dam and doubled the depth of the chin spoiler for increased radiator airflow. The big-blocks ran hot but didn’t overheat. Compared to the Sting Ray, the new car added 100-pounds, was 7-inches longer, the front/rear track was wider, the width was the same, and the height 2-inches lower. The stylists and designers were happy with the translation from show car to the production car, although the interior and trunk was smaller.

The press preview were very well, but when production cars arrived, it wasn’t pretty. The December ‘67 issue of Car and Driver thrashed the car and canceled the road test because their 2000-mile test car was literally falling apart. Body panels were too loose or too tight, the fiberglass was wavy, doors and locks were stiff. There were rattles, water leaks, a loud resonance at idle, an overheating engine, and other problems – 48 in total. Later when they tested an improved 400-hp 427 model they commented, “A brilliant car with all the virtues and vices of an American car.” Car Life said, “Who needs LSD with something like this to get high on?” It seemed that Motor Trend’s “Sports Car of the Year” was a little premature.

Perhaps buyers didn’t catch Car and Driver’s scathing initial review. By the end of the ‘68 run, a new Corvette sales record was set with 28,566 units sold – 9,936 coupes and 18,630 convertibles. At $4,663 for the coupe and $4320 for the convertible, the $275 and $80 respective price increases seemed like a bargain for such an exotic-looking Corvette. Had the ‘67 model been carried over as a ‘68 model to allow more time to groom the car, would it had sold 28,566 units? Probably not. But it was not something Chevrolet would ever try again.- KST

The above 11×17 Parchment Paper Print is available for just $24.95 + $6.95 S&H. Each print is signed and numbered by the artist. You can order your with the secure PayPal button below, or by calling 1-800-858-6670, Monday through Saturday 10AM to 9PM Eastern Standard Time.

The above 11×17 Parchment Paper Print is available for just $24.95 + $6.95 S&H. Each print is signed and numbered by the artist. You can order your with the secure PayPal button below, or by calling 1-800-858-6670, Monday through Saturday 10AM to 9PM Eastern Standard Time.

The above 11×17 Parchment Paper Print is available for just $24.95 + $6.95 S&H. Each print is signed and numbered by the artist. You can order your with the secure PayPal button below, or by calling 1-800-858-6670, Monday through Saturday 10AM to 9PM Eastern Standard Time.

The above 11×17 Parchment Paper Print is available for just $24.95 + $6.95 S&H. Each print is signed and numbered by the artist. You can order your with the secure PayPal button below, or by calling 1-800-858-6670, Monday through Saturday 10AM to 9PM Eastern Standard Time.

The above 11×17 Laser-Etched Print is available for just $44.95 + $8.00 S&H. Each print is hand-made on 11×17 brush-finished metalized-mylar . You can order your with the secure PayPal button below, or by calling 1-800-858-6670, Monday through Saturday 10AM to 9PM Eastern Standard Time.

The above 11×17 Laser-Etched Print is available for just $44.95 + $8.00 S&H. Each print is hand-made on 11×17 brush-finished metalized-mylar . You can order your with the secure PayPal button below, or by calling 1-800-858-6670, Monday through Saturday 10AM to 9PM Eastern Standard Time.

Here’s the BEST way to keep up with K. Scott Teeters’ Corvette blog!