A Look Back at Chevrolet’s Experimental, Prototype, Concept Car, and Show Car Corvettes

By Scott Teeters as written for Vette Magazine and republished from SuperChevy.com. Read the other experimental stories HERE.

General Motors makes hundreds of kinds of cars and trucks. Some sell hundreds of thousands of units a year, which makes Chevrolet’s Corvette a complete enigma. Given the small number of Corvettes sold every year, it is a modern American manufacturing miracle that the car survived for 61 years.

The Corvette was “officially” born on January 17, 1953 at the GM Motorama Show at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel, in New York. To understand the impact of Harley Earl’s two-seater sports car concept car, you have to look at typical cars of 1953. The car was low and sleek, and wasn’t over festooned with styling gimmicks. Based on the response from attendees, Chevrolet rushed the car into production, and the rest is history.

Today, the Corvette is GM’s flagship car. When Chevrolet unleashes a new Corvette, the automotive world stops to take notice. But things were not always this way. Up to the C4, there were many inside GM that wanted to see the Corvette go away. For the first 20-some years, the car suffered from an identity crisis. Inside GM there were always those that wanted the Corvette to be something different; a lightweight sports car, a mid-engine car, a rear-engine car, a four-seater personal luxury car, powered by a boxer-type flat-six, Wankel rotary-powered, turbocharged small-displacement hemi-headed double-overhead cam powered, and even an all-aluminum car. Chevrolet kept the loyal faithful stoked with two or three experimental, prototype, show car Corvettes per year. From an enthusiast’s perspective, this was endlessly fascinating.

This is part eight of a chronological look back at Chevrolet’s high-profile experimental, prototype, concept car, and show car Corvettes. Some of the cars had exotic names such as, “Astro I,” “Astro-Vette” and “Geneve.” Others had experimental prototype numbers, such as “XP-700” and “XP-882.” And some had sexy names, such as, “Nomad,” “Mulsanne,” “Snake Skinner,” “Mako Shark,“ and “Tiger Shark.” In retrospect, a few of the cars were the shape of things to come, but most were simply, “Here’s an idea of something we’re working on.” Either way, it was all a ton of fun!

1967 Astro I

From 1960 to 1976, Chevrolet R&D and Chevrolet Styling built 11 functional mid-engine “Corvettes.” The first three (CERV I, CERV II, and GS-IIB) were in truth cloaked race cars. The CERV I was an Indy car. Duntov envisioned the CERV II as a street GT to counter the Ford GT40, but then again, Zora always wanted “more.” And the GS-IIB became a Chaparral. The XP-819 rear-engine layout didn’t have a snowball’s chance. Considering the limitations of the bias-ply tires of the day, the concept of a mid-engine performance car made sense—it was about weight balance. Cutting-edge European sports and race cars were going mid-engine and even Indy cars had the engine in the middle, so why not the Corvette?

Now, one might think that GM’s divisions are all one happy family. But, back in the day they were often fierce rivals. In 1953, Pontiac, Buick, and Oldsmobile wanted a piece of the new Corvette action and built their own two-seaters, but quickly dropped them because it looked like the Corvette was a total loser. Then in 1964, Pontiac tried again to launch a two-seater sports car with the Banshee concept that became the Opel GT in 1968. Even inside of Chevrolet there was two-seater competition from the Corvair group with the beautiful 1963 mid-engine Monza GT and the rear-engine Monza SS Roadster. It was all quite a swirl of concepts and competition.

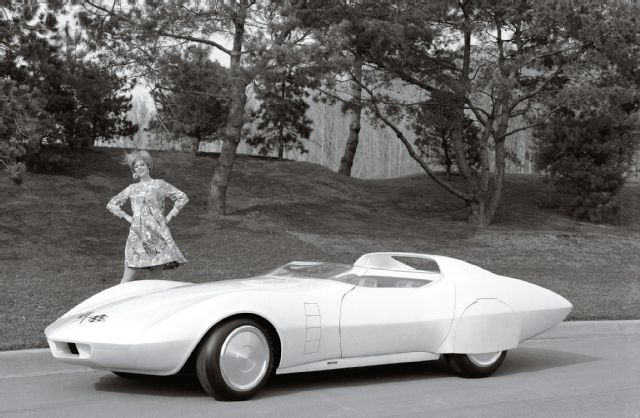

The Astro I was altogether something else. Designers create hundreds of sketches, dozens of color renderings, and a few clay models. But sometimes ideas need to be fleshed out as a real car. The Astro I was one such concept car. Perhaps chief of styling Bill Mitchell asked, “How low, can we go?” The Astro I may well be the lowest concept car Chevrolet ever built, measuring just 35.5 inches in height. Viewed alone, the car looks big, but it is astonishingly short, small, and pointed. The Mako Shark “look” was all the rage and the Astro I nose carried that look to the extreme. Since the engine was amidships, there was no traditional front hood. Instead, there was a hatch opening within the large stinger on the top of the front end to access the master cylinder, battery, and windshield washer. Atop the roof is a three-element rearview periscope because there’s no rear window! The rear roof section beautifully tapers back into a C2 Sting Ray coupe look, but without the glass. On the rear deck there are two heat vent grilles and close to the rear leading edge are two air-brake flaps. At the back end, the taillights were hidden behind simulated air vents and the license plate is recessed with a chrome surround.

As if all this isn’t unusual enough, getting in and out is even more unique. The entire rear section of the Astro I is a big clamshell, hinged at the back that lifts up, with the bucket seats attached for ingress and egress. Practicality be damned! It’s a concept car. Since the seating is almost horizontal, the interior looks “head-to-toe” bucket seats. Twin handgrips replace a steering wheel and there’s a control pod to the left of the handgrips. The view from inside must have been somewhat … frightening.

The suspension and running gear was interesting, too. The four-wheel independent suspension had lightweight control arms and four-wheel disc brakes. The wheels don’t have hubcaps, but instead, they’re eight-bolt magnesium centers with a removable outer rim to vary the width. The wheels measured 5.5 inches on the front and 7 inches on the back, shod with prototype Goodyear redline tires. The flat-six Corvair variant engine was most interesting. They could have used a stock Corvair engine, but instead built what should have been in the production Corvair. The little aluminum six-banger had hemi-heads with inclined valves, a belt-driven single-overhead cam (SOHC), and two GM prototype inline three-barrel carbs with Weber internals that looked just like Weber’s.

Like the ’10 Stingray Concept, there was never a published report of what it was like to drive the Astro I. If the car was ever driven on one of GM’s test tracks, acceleration and top speed results were never published. This tells me that the car was never given the “Let’s see what this baby will do” tests. So that means Duntov probably didn’t get to drive the car. The good news is that the Astro I is still around and part of the GM Heritage Collection. Sometimes designers just need to try out ideas for real. While the car certainly looks dated, it still looks good.

1968 Astro II

Within the narrative of early Corvette history, men such as Bill Mitchell, Ed Cole, and Zora Arkus-Duntov cast very long shadows over the storyline. While these and several other men definitely steered the direction of the Corvette based on their vision, in no way did they design every aspect of the Corvette. While Duntov got the lion’s share of attention for pushing the mid-engine effort, there was another power-player that was all but invisible to the public: Chevrolet’s Chief of Engineering Frank Winchell. If you are new to the Corvette hobby you might be thinking, “Frank, who?” Many inside GM and Chevrolet wanted to design Corvettes, and Frank had some unusual design perspectives. The Astro II was Winchell’s third and final mid-engine Corvette-type car. (We covered Winchell’s GS-IIB and his XP-819 V-8 rear-engine experimental in Part 6 of this series.) Unlike Duntov, Winchell was comfortable being a low-profile corporate man. He felt that he could get more done that way. Those that worked with both men said that while Duntov managed with love and enthusiasm, nobody worked “with” Winchell, they worked “for” him. While Zora and Frank respected each other, they often locked horns over design concepts.

By 1968, mid-engine mania had gripped Ford and even American Motors. When Chevrolet learned that Ford was developing the Mach II mid-engine Mustang, they just had to do something. Of all of the Winchell mid-engine Corvette concepts, the XP-880 was the closest to a production design. It’s also worth noting that the XP-880/Astro II started out as an engineering study that worked out well. Good enough to get some flash and trim and a cool-sounding name, then sent out to work the show car circuit. The Astro II’s “engineering study roots” show up in the fact that the car has no headlights and the interior is bland and not “designed and styled.” The car’s target weight was 3,200 pounds, powered by a big-block L36, coupled with a two-speed automatic transaxle from a Pontiac Tempest, and 60 percent of the weight on the rear wheels.

Unlike in the XP-819, the L36 427 engine in the Astro II was placed ahead of the rear axle and turned 180 degrees so that the accessory parts would hang off the back of the engine. The water pump was gear-driven off the camshaft at half speed. The aluminum radiator was placed behind the transaxle, connected to the engine with long connecting hoses. Airflow to the radiator came from intakes on the rear deck.

A steel backbone frame was created with a 20-gallon fuel bladder placed inside the center backbone. To make the car more realistic from a production standpoint, suspension and brake components were off-the-shelf pieces that included Camaro lower front wishbones, knuckles, spindles, and brake rotors with Corvette calipers. The upper wishbones and coilover shock assemblies were fabricated. The rack-and-pinion steering was mounted below and in front, and the antiroll bars were mounted above the suspension. At the rear, a very large upper wishbone controls thrust drive and brake torque and a Corvette transverse leaf spring was used. The halfshafts used Olds Toronado universal joints at the inner ends. The two-speed automatic transaxle came from a ’63 Tempest and was admittedly the weak point.

Stylists did a great job of making the XP-880 look like a Corvette. The roof looked like the new C3 and the front and rear fender humps definitely said “Corvette.” Unlike the ’67 Astro I, the ’68 Astro II’s initial track testing proved that the design had real potential, even though it was riding on relatively narrow, bias-ply E70x15s up front and L70x15s on the rear. Steering was astonishingly slow, 23.6:1. Unlike Winchell’s two previous mid-engine Corvettes, this one was close to right, but was in serious need of development.

Painted Fire Frost Blue and dressed up with badges, the Astro II was sent off to the 1968 New York International Car Show. Many said that the XP-880/Astro II seriously upstaged the Mach II. Ultimately, the concept was rejected for three reasons. First, tooling cost would seriously add to the sales price. Second, Chevy had just spent a ton creating the all-new interior and body for the C3, And third, the new ’68 Corvette hit a new sales record with 28,566 units sold. It wasn’t broke so Chevrolet wasn’t about to fix it.

1968 Astro-Vette

Show car Corvettes usually get gushed all over. But the 1968 Astro-Vette is arguably the most disliked Corvette show car Chevrolet ever dished up. You can almost hear this car saying, “Don’t hate me … I’m still a Corvette.” Oftentimes, the point of a “show car” Corvette is exaggeration. The 1960 XP-700 and 1961 Mako Shark I were perfect examples of exaggeration. So what was the point of the Astro-Vette? Chevrolet stated that it was an exploration of aerodynamics. OK, so why didn’t they wind tunnel test the Astro-Vette? And while there were obvious land-speed record-type styling elements, there were some problems more glaring that the pearl white paint. But let’s back up a little to the late ’60s for some perspective.

While stylists had been “streamlining” cars since the early 1930s, the emphasis was on reducing wind drag. It wasn’t until the mid-’60s when road racers such as Jim Hall started the exploration of front and rear spoilers, airfoils, and wings to manage airflow for the benefit of performance. By the late ’60s, factory muscle cars were using chin spoilers and rear deck spoilers or wings. On the street these appendages did little to nothing, but on a racetrack they worked wonders.

C2 Corvettes always had a front end lift problem at high speeds. The new ’68 Corvette had a small chin spoiler and a slight spoiler at the back end, but the car still had lift problems. What no one was looking at was the air flowing under the car. Then, add in the Corvette’s rear end squat, and you have a floaty front end at speed.

Considering what was known in 1968, the Corvette stylists did an admirable job. The Astro-Vette started life as a blue-on-blue ’68 Corvette coupe with a 427/400 engine and three-speed Turbo-Hydramatic. The car received zero performance enhancements. This was strictly a styling exercise. The front was seriously extended, close to that of the Mako Shark II and the front grille opening was reduced like a Bonneville racer might be. The production chin spoiler was not added. We all know the ’68-’72 Corvette big-block domed hood. So, where’s the dome for the big block engine? There’s a very subtle center section rise that begins close to the leading edge of the nose that runs back to the windshield. This is probably where the ’73-’99 hood came from. And what should be a bumper appeared to be completely faired in with the body. They might have been thinking of an Endura front bumper for the Corvette. On the front fenders what looked like possible vent flaps were actually only scribe lines. The cut-down windscreen was straight off the road racing track and while reducing the overall frontal area, it wasn’t doing much for aerodynamics since the interior was open.

The B-pillar is very cool. It’s been chopped and shaped into an airfoil. Bringing up the rear, the side skirts that were intended to smooth out the airflow were a “love ’em or hate ’em” kind of thing, and were generally not well received. The smooth wheel covers were also a throwback to the olden days of streamlining. The back end was seriously tapered and actually looks like an exaggerated version of what we saw on the ’74 Corvette’s rear bumper cover. The same look was later applied to the Manta Ray show car. Taillights were non-traditional horizontal slats. The original blue interior was died black and completely stock, except for a racing steering wheel.

Out on the show car circuit, the Astro-Vette went over like a belch in church and was quickly relegated to secondary car shows. The Astro-Vette was nicknamed “Moby Dick.” NOT a compliment. It wasn’t long before the car was put into solitary confinement long-term storage. Somewhere along it’s lifeline the car was painted orange. It’s best we didn’t have to see that. Then in 1992 the car was refurbished to its original configuration.

So, what would have helped? A few things; the car should have been lowered and given a slight forward rake with the front end drooping down a little. Lakes pipes should have graced the sides. The entire roof section should have been similar to the ’69 Manta Ray. Functional front fender flaps would have been nice, as well as a real, full bellypan. Then the car should have been wind tunnel tested and taken to Bonneville, powered by a 427 ZL1 engine with very tall gears. A national speed record would have added credibility. And lastly, repainted Rally Red, Le Mans Blue, or Silverstone Silver.