Words and Art by K. Scott Teeters as written for Vette magazine and republished from SuperChevy.com

A look back at Chevrolet’s experimental, prototype, concept car, and show car Corvettes

General Motors makes hundreds of kinds of cars and trucks. Some sell hundreds of thousands of units a year, which makes Chevrolet’s Corvette a complete enigma. Given the small number of Corvettes sold every year, it is a modern American manufacturing miracle that the car survived for 61 years.

The Corvette was “officially” born on January 17, 1953 at the GM Motorama Show at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel, in New York. To understand the impact of Harley Earl’s two-seater sports car concept car, you have to look at typical cars of 1953. The car was low and sleek, and wasn’t over festooned with styling gimmicks. Based on the response from attendees, Chevrolet rushed the car into production, and the rest is history.

Duntov in the Racing Pits

Today, the Corvette is GM’s flagship car. When Chevrolet unleashes a new Corvette, the automotive world stops to take notice. But things were not always this way. Up to the C4, there were many inside GM that wanted to see the Corvette go away. For the first 20-some years, the car suffered from an identity crisis. Inside GM there were always those that wanted the Corvette to be something different; a lightweight sports car, a mid-engine car, a rear-engine car, a four-seater personal luxury car, powered by a boxer-type flat-six, Wankel rotary-powered, turbocharged small-displacement hemi-headed double-overhead cam powered, and even an all-aluminum car. Chevrolet kept the loyal faithful stoked with two or three experimental, prototype, show car Corvettes per year. From an enthusiast’s perspective, this was endlessly fascinating.

This is the part nine of a chronological look back at Chevrolet’s high-profile experimental, prototype, concept car, and show car Corvettes. “Racing” has lead the way in the design and development of the Corvette ever since January 1956 when Zora Arkus-Duntov took a modified 1956 Corvette to Daytona Beach and racked up a two-way average speed of 150.583 mph. This was the opening act for the Daytona Speed Weeks event the following month where Zora then took three heavily modified ’56 Corvettes and put the Corvette on the map, with driving help from John Fitch and Betty Skelton.

The die was cast and street Corvettes would forever be linked to racing Corvettes. After GM decided to adhere to the AMA mandate that car makers not participate in racing, Duntov always made sure Corvette owners had the right hardware if they wanted to race their Corvette. To facilitate the production of his “racer kits,” engineering development cars (race cars) had to be made. Here are Duntov’s last three racer kit development cars. Very little info, and even fewer pictures exist of these cars, which is a real shame.

Duntov’s 1969 427 ZL1 A/Production Racer

Roger Penske stunned the ranks in 1966 when he entered a preproduction aluminum-headed 427 L88 ’66 Corvette coupe in the 24 Hours at Daytona race. The following year, RPO L88 was on the ’67 Corvette order form. The L88 was a full-package: engine, heavy-duty drivetrain, suspension, plus a few weight-saving deletes. And best of all, it was a work-in-progress, with the ultimate goal of offering an all-aluminum version of the big-block engine.

The prospect of massive amounts of big-block horsepower and torque, at small-block weight was irresistible. The all-aluminum engine was on Duntov’s “wish list” since 1957 as part of his proposal for the Q-Corvette that also included fuel injection and a transaxle—sound familiar? The all-aluminum small-block was tried in the early ’60s within the Grand Sport program. Unfortunately, the basic small-block, while strong enough as a cast-iron piece, wasn’t designed to cast in aluminum and then race. However, for the Mark IV big-block, it was a piece of cake. The ZL1 engine made its debut on the cover of the December 1968 issue of Hot Rod magazine, followed by the baddest-looking racing Corvette seen since the modified version of the 1963 Grand Sport.

In the summer of 1968 when the automotive press arrived at the Milford test facility to preview the ’69 cars, they weren’t prepared for Zora’s latest toy: the ZL1-powered 427 Corvette. But this wasn’t like the ’63 Z06 Corvette that looked like any other “regular” ’63 Corvette. This thing screamed “RACE CAR!” The only thing missing from Zora’s white ZL1 Corvette was sponsor decals and numbers. The car had killer looks and grunt to match it.

The objective was simple: take one L88 Corvette roadster, plus select aftermarket performance hardware, and build it like a racer would. Everything that didn’t belong on a race car was removed. When completed, Duntov and his crew had reduced the weight of the car by about 400 pounds to approximately 2,965 pounds—the ZL1 engine by itself saved 175 pounds. Missing production items included the radio, heater, insulation, headlights, radiator shroud, upholstery, rear bumpers, and cast-iron exhaust manifolds. Racing equipment included 9.5-inch wide magnesium wheels, shod with 10.5-15 front and 12.5-15 Goodyear racing tires, the ZL-2 cold-air induction hood (aka, the L88 hood) with hood pins, and L88 fender flares. Header side-pipes essentially uncorked the potential of the radical, “off road” ZL1 engine. This must have been a fun project for the young engineers. Duntov himself gave journalists “believer rides.” When coaxed to make a drag racing run, Zora clicked off a 12.1 e.t. at 116 mph using 3.60:1 gearing. Lower 4.11:1 or 4.88:1 gearing, with drag racing-style speed-shifting would have surely put the car into the low-11s.

Later at GM’s Phoenix test track, journalists got to actually drive the white ZL1 on a short road course. Road & Track described the car’s performance as being “close to a Group 7 racecar” they had driven shortly before. Earlier, Zora had the hood blow off while performing a speed test at 180 mph! Duntov’s quasi-ZL1 racer was a shining example of the ZL1’s potential. How unfortunate that the L88/ZL1 wasn’t made as a separate Corvette model, similar to what was done with the C5 Z06 and then the wide-body C6 and C7 Z06. Duntov explained the reason the fender flares were separate pieces that came with the cars in the trunk area. At the St. Louis assembly plant, Corvette bodies were held in a jig and then lowered onto the chassis, and Chevrolet couldn’t justify a separate jig just for a few hundred race cars.

After the initial splash, Duntov’s quasi-A/Production ZL1 race car disappeared. Many asked what became of the car, but no real answers have ever been found. Most likely, the good parts were removed and the rest of the car was destroyed. Otherwise, Chevrolet would have surely shown it at the big Corvette shows. However, Kevin “Mr. L88” Mackay is considering building a replica of the car. Considering all of the early Corvette racers Mackay’s shop, Corvette Repair, has restored, he’d be Da’ Man.

1969 454 ZL-1 Drag Corvette – The Great Pumpkin

Also on hand the summer of 1969 as part of the ’70 press preview was a menacing looking Monaco Orange Corvette wearing 10.65-inch drag racing slicks. The car was there the year before as a “regular ZL1.” Engineer Gib Hufstader said that the only purpose for cars such as this was to impress the reporters. Forty-six years later we’re still talking about this!

The heart of this drag Vette was its experimental LT-2 engine—essentially a bored, all-aluminum 427 ZL1. The engineers tinkered with compression ratios, valve seat angles, and the intake manifold was modified to accept a huge Holley 4500 NASCAR carb rated at 1,400 cfm. Most interesting was the 180-degree header system that paired cylinders that fired 180-degrees apart. The system didn’t work any better than regular drag headers with collectors, but sounded like an Indy or Le Mans racer. Everything else under the hood was pretty much stock L88, which is already a lot.

To make life easier for journalists, a Turbo 400 automatic transmission with a 2,800-rpm, high-stall torque converter was used. Drag racing 4.88:1 gearing ensured quick, off-the-line acceleration. Those lucky enough to be on hand weren’t prepared for the awesome power of this uncorked, big-block. To manage rear-wheel hop, the car had the F-41 rear spring with two leafs and F-41 shocks. A 2-inch metal block was mounted to the top of the hub carrier, which after traveling 2 inches met a 3-inch rubber bumper. The American Mags—8.5-inch in the back—were shod with 10.65xXS-12 Racemaster slicks and the 7-inch wheels on the front were shod with stock tires. Gib Hufstader did the transmission work and Tom Langdon built the LT-2 engine that, according to Gib, produced 584 horsepower (which seems a little low)!

How good was the 1,320 ride? There were a total of 71 runs, with a best run of 10.89 at 130 mph and an average of 12.13. Trap speeds are an indicator of plenty of power. Why the soft average e.t.? Most guys just smoked the Racemasters—a real e.t. killer. Proving Grounds PR guy, Bob Clift said, “We all enjoyed driving that car. That was back in the good old days, Zora used to keep us all excited back then. We were revving it up to 6,000 rpm, then dumping it into gear (a neutral start). It took off like a stripped-ass ape!” After the fun was over and the transmission was pulled, engineers found stress cracks where the flywheel attached to the crank. It was about ready to let go! A similarly equipped ZL1 Camaro prepared by Dick Harrell ran 10.21 at 133 mph at Kansas City International Raceway. It seems unbelievable that GM would allow something like this to happen—letting auto writers drive a monster car such as this.

The obvious next question is: what happened to the mighty LT-2 454 Corvette? Odds are that after the event, the good parts were removed and the rest sent to the crusher—the usual fate for cars such as this. But lament not! The car was covered in October 1969 issue of Motor Trend magazine and left a lasting impression on Dave Miller, of Shell Beach, California. Dave traced the serial number of the engine back to Corvette engineer and enthusiast Kevin Lambert, in Michigan. Lambert arranged a dinner with Miller and former Chevrolet engineers Gib Hufstader and Tom Langdon. By the end of dinner, Miller was convinced to build a replica.

Dave’s replica is very close to the original, right down to the 180-degree headers. Werner Meier, of Masterworks Automotive Services, in Madison Heights, Michigan, performed the construction of the replica. They even replicated the “rough around the edges, cobbled together” look. The 454 LT-2 clone pulls a little stronger than the original—624 hp on the dyno and has run a best of 10.84 at 124 mph. Such is the passion that these kinds of one-off Corvettes inspire in the Corvette community.

Duntov’s Last Corvette Racer Kit – Batmobile

In 1974, Zora Arkus-Duntov was one year away from GM’s mandatory retirement age of 65. Twenty-one years before, Zora saw Harley Earl’s Corvette at the 1953 Motorama and later said that it was the most beautiful car he’d ever seen. It’s what motivated him to seek employment at GM. The only job he was interested in was to be an engineer on the Corvette. Knowing that his time at GM was limited, Duntov wanted to do one last Corvette “racer kit.”

The L88 racer kit, and later the all-aluminum 427 ZL1, was a huge success that brought a lot of racing glory to Corvettes from 1967 through the early ’70s. It was also a time of tremendous advancements in racing technology. Road racing cars were running on tires that were unimaginable just 10 years before. The factory L88 flares were adequate, but the tires were getting too big for the big fender bulges. In the early ’70s, John and Burt Greenwood were the lead guys in Corvette racing, taking the cars into the realm of “purpose-built” race cars. Many were asking of the Greenwood cars, “It looks like a Corvette, but besides the engine, where’s the Corvette?” Ever the innovator, John Greenwood suggested to Duntov that a widebody kit could be developed that would cover the widest tires and generate additional downforce. Enter Duntov’s final “racer kit” —the widebody.

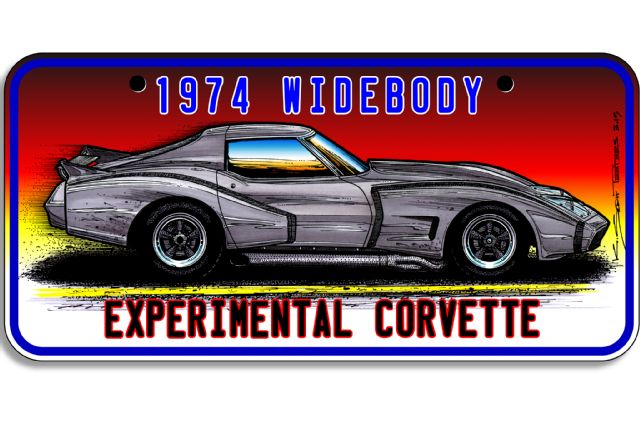

Duntov called it his “silhouette racer” and set Randy Whittin at GM Design to the project. The front fenders were wedge-shaped and fanned out to the front edge of the doors. The rear fenders were also wedge-shaped and ballooned into large pontoon shapes, large enough to cover 20-inch-wide slicks. An adjustable wing was added to the back for additional downforce. Whereas in the early ’60s race car designers were concerned with reduced frontal area, with massive amounts of horsepower and huge sticky tires, “downforce” was the new objective. With huge racing tires, broad shoulder fenders, and a deep front air dam, the look was beyond menacing. Diversified Glass Company made the prototype parts and the widebody kit was included in the Chevrolet Power Manual. Greenwood then contracted with Diversified and started selling body kits as part of his burgeoning Corvette race car business.

Of course, it all starts with an engineering prototype. While not an all-out race car like the ’69 car, it was close enough to make the troops stand back! The mule car was based on a production ’74 Corvette and was powered by a balanced and blueprinted cast-iron ZL1 variant with open-chamber heads, header side pipes, a big Holley double-pumper carb, and the L88 cold-air induction hood. Clear plastic headlight covers over quartz-iodine headlights were used and oil coolers were behind the mesh-covered front grille openings. The body kit parts were riveted to the stock body and the seams covered over with 200-mph duct tape. Lowered and wearing magnesium racing wheels and tires, this was one bad-ass-looking Corvette with that “cobbled together” look.

Marty Schorr (founder and first editor of Vette magazine) was the editor of CARS magazine at the time. As the editor of a popular enthusiast magazine and partners with Joel Rosen’s Baldwin Motion Super Cars enterprise, Marty had a nice working relationship with Duntov. One day while visiting Duntov in Detroit, Marty got a ride in Zora’s latest and last Corvette beast. As Marty tells the story, “One day, he took me out on the high-speed oval test track. We were going full-tilt, with the tail slightly out, while he had a cigarette in his mouth, explaining suspension geometry and big-block engine development! He had great control of this animal car. He was so ‘out there’ that many times he was banned from the test track.”

There was no published record of the prototype’s performance, and aside from CARS magazine and later Vette Quarterly (Vette magazine’s original name) Duntov’s “silhouette racer” got little attention, but the Greenwood brothers “Batmobile” sure did.

Overnight, almost all road racing C3 Corvettes were wearing the widebody kit. Greenwood’s Sebring ’75 Corvette holds the official all-time highest speed on the banking at Daytona International Speedway of 236 mph, set on February 2, 1975. And what of Duntov’s engineering prototype? Like Zora’s white ’69 ZL1, it was never seen again after 1974. Most likely, the good parts were removed and the rest sent to the crusher. While the car holds a prominent place in this series of experimental and prototype Corvettes, because it had so little attention and is so relatively unknown, to date there have been no published reports of a replica in the making. Attention builders! Here’s an opportunity for you!