The 1962 Monza GT – Corvair-based, Mid-Engine Sports Car – Think Porsche 550/1500 RS Spyder and you’re close!

By the early 1960s the Fuelie Corvette, equipped with Duntov’s “Racer Kit” suspension and brake packages, established itself as a solid, dependable platform for a B/Production or A/Production SCCA racer. Several cars had killer reputations on the track, including; the Nickey Chevrolet-sponsored 1959 “Purple People Eater” driven by Jim Jeffords, Dave MacDonald’s “Don Steves Chevrolet” C1 Corvettes, C1s raced by Dick Thompson and Dick Guldstrand, as well as Grady Davis’ 1961 B/Production and 1962 A/Production “Gulf Oil” Corvettes, and others. Setup right, these cars could be unbeatable.

By the early 1960s the Fuelie Corvette, equipped with Duntov’s “Racer Kit” suspension and brake packages, established itself as a solid, dependable platform for a B/Production or A/Production SCCA racer. Several cars had killer reputations on the track, including; the Nickey Chevrolet-sponsored 1959 “Purple People Eater” driven by Jim Jeffords, Dave MacDonald’s “Don Steves Chevrolet” C1 Corvettes, C1s raced by Dick Thompson and Dick Guldstrand, as well as Grady Davis’ 1961 B/Production and 1962 A/Production “Gulf Oil” Corvettes, and others. Setup right, these cars could be unbeatable.

Yet, despite their track success, the European sports car community did not accept the early Corvettes. Why? Because Corvettes were big and heavy, compared to European sports cars. Traditionalists considered Corvettes to be crude, with more in common with a Chevy Bel Air than anything from Porsche, Ferrari, Maserati, Jaguar, Aston Martin and other low-volume European exotics. Corvettes were “mass produced” while European sports cars were “hand-crafted.” This perception did not go unnoticed inside Chevrolet, and some were thinking of a “Plan B” for the Corvette.

Yet, despite their track success, the European sports car community did not accept the early Corvettes. Why? Because Corvettes were big and heavy, compared to European sports cars. Traditionalists considered Corvettes to be crude, with more in common with a Chevy Bel Air than anything from Porsche, Ferrari, Maserati, Jaguar, Aston Martin and other low-volume European exotics. Corvettes were “mass produced” while European sports cars were “hand-crafted.” This perception did not go unnoticed inside Chevrolet, and some were thinking of a “Plan B” for the Corvette.

The Monza GT and the Monza SS roadster were never intended to be replacements for the Corvette. After all, the basic platform was the rear-engine Corvair. Now before you go, “Puke! Puke!” lets go back to 1957 for a brief look at where the Corvair came from, Chevrolet General Manager, Ed Cole’s aggressive and innovative, “Q-Chevrolet” line of cars.

Cole was an engineer, corporate “car-guy” and he liked and appreciated fast cars. In the 1940s and 1940s “fast cars” were looked down upon as things for reckless ruffians, hoodlums, mobsters, moonshiners, and daredevils. For an engineer working for stuffy General Motors, Cole definitely had an edge. His first big success was as lead designer of the Cadillac OHV engine that was later used as the basic design platform for the small-block Chevy engine that turned the performance world upside-down.

Cole was an engineer, corporate “car-guy” and he liked and appreciated fast cars. In the 1940s and 1940s “fast cars” were looked down upon as things for reckless ruffians, hoodlums, mobsters, moonshiners, and daredevils. For an engineer working for stuffy General Motors, Cole definitely had an edge. His first big success was as lead designer of the Cadillac OHV engine that was later used as the basic design platform for the small-block Chevy engine that turned the performance world upside-down.

Cole loved new mechanical innovations and technology and after becoming the General Manager of Chevrolet, Ed wanted to do something really big. He envisioned the entire 1960 Chevrolet line of cars being equipped with a “transaxle” and he called the new line, the “Q-Chevrolet.” With the transmission hump eliminated, the interior could be opened up – especially on the full-size Chevrolet. “Roomy” was a marketing position in the 1950s. Also, putting the transmission together with the rear axle would move more weight to the rear, and improve traction and handling. Cole was definitely thinking in the right direction.

Because Cole’s mandate was that ALL Chevrolet cars used a transaxle, and since the Corvette was part of the Chevrolet line, designers worked out the basics of a “Q-Corvette.” In hindsight, this was a prehistoric C5 Corvette. Imagine a 1960 Corvette wearing a “Sting Ray” like body, with four-wheel independent suspension, disc brakes, an all-aluminum fuel-injected engine, a dry-sump oil system, and a transaxle. Yes, it was a C5, 37 years early!

Unfortunately for Cole, the Q-Chevrolet concept collapsed due to cost, but the transaxle survived and went into production in GM’s new VW Beetle-fighter, the Corvair. From the timeframe of 1960, the little Corvair was a pretty cool car: rear-engine, four-wheel independent suspension, a transaxle, and an all-aluminum opposed, flat-six engine. Styling was definitely “late ‘50s and sold fairly well from the start. In 1960 Chevrolet produced 253,268 Corvairs. 1961 turned out to be the Corvair’s best year with 337,371 units built, followed closely in 1962 with 336,005 Corvairs sold. 1963 to 1966 was a downward slide: 288,419 in ’63, 215,300 in ’64, 247,092 in ’65, 109,880 in ’66, with the bottom dropping out in ’67 with just 27,253 cars, ’68 saw just 15,399 Corvairs, and the final year was a paltry 6,000. Even the restyling of the ’65 model didn’t help. The reason for this is well documented and another story.

Unfortunately for Cole, the Q-Chevrolet concept collapsed due to cost, but the transaxle survived and went into production in GM’s new VW Beetle-fighter, the Corvair. From the timeframe of 1960, the little Corvair was a pretty cool car: rear-engine, four-wheel independent suspension, a transaxle, and an all-aluminum opposed, flat-six engine. Styling was definitely “late ‘50s and sold fairly well from the start. In 1960 Chevrolet produced 253,268 Corvairs. 1961 turned out to be the Corvair’s best year with 337,371 units built, followed closely in 1962 with 336,005 Corvairs sold. 1963 to 1966 was a downward slide: 288,419 in ’63, 215,300 in ’64, 247,092 in ’65, 109,880 in ’66, with the bottom dropping out in ’67 with just 27,253 cars, ’68 saw just 15,399 Corvairs, and the final year was a paltry 6,000. Even the restyling of the ’65 model didn’t help. The reason for this is well documented and another story.

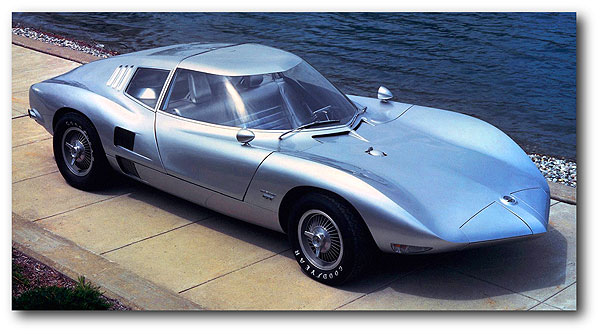

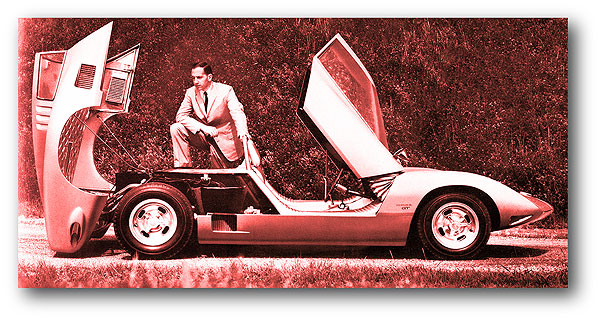

But at the height of the Corvair’s popularity, V.P. of Design, Bill Mitchell saw “potential” in the Corvair’s unique platform and set two of his sharpest designers to work on a radical Corvair; Larry Shinoda and Tony Lapine. Two cars were built; the Monza GT was a mid-engine coupe and the Monza SS was a rear-engine open-roadster. Neither car looked like anything else on the road, let alone a Corvair. If you ever wondered where the big front fender humps on the Mako Shark-II came from, now you know!

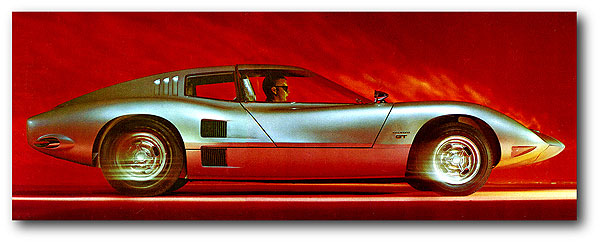

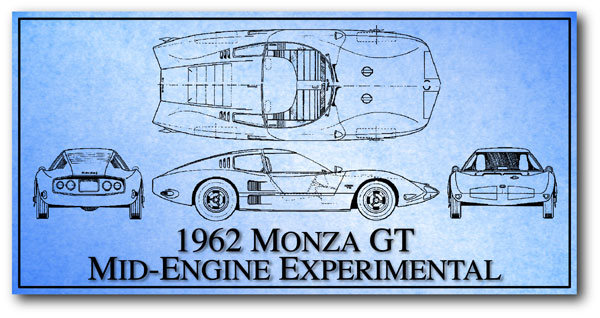

The Monza GT coupe is arguably the more interesting of the two concepts because of its mid-engine layout. The Corvair drivetrain was turned 180-degrees so that the engine was behind the driver and in front of the rear wheels – just like an exotic European sports car. The Monza’s engine was a stock, Corvair engine (148-CID / 102-HP) and four-speed manual transaxle. Since this was just an overall concept, the engine wasn’t enhanced for performance. The Monza GT had four-wheel independent suspension, four-wheel disc brakes, and alloy wheels. This was pretty heady hardware for 1962! Its too bad the Chevy guys didn’t put more, “grunt” into the Monza GT’s engine. Had they done so, I’m sure there would have been a demand for such a car.

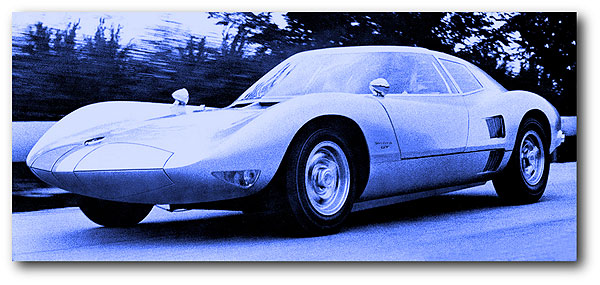

About the body design; WOW! Where did Shinoda and Lapine come up with this one? This is 1962, three years before the debut of the Mako Shark-II. The family resemblance is obvious. Also, by this time, Shinoda had most likely completed his work on the new Sting Ray. Larry had a peach-of-a job working on Bill Mitchell’s pet projects. So by 1962 he’d spent several years styling what was to become an American automotive icon. Shinoda was comfortable drawing bold, swooping shapes that were dynamic.

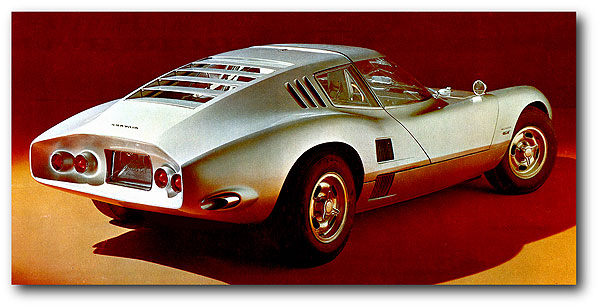

Bill Mitchell’s affection for crisp, sharp lines (like a freshly pressed men’s suit) is evident with long smooth curves, crisp surface breaks, blended with sharp edges in the front and back. Even the windshield on the Monza GT has a crease down the center. (“Creased” glass wouldn’t arrive on a GM car until the 1967 Cadillac Eldorado and later the 1973 Chevy Monte Carlo and Pontiac Grand Prix) The curves and creases are so beautiful it’s easy to not notice that there’s no A-pillar! Now unless they were planning to use “transparent aluminum,” this was never going to happen in a production car. But, that’s what concept cars are all about. “Pie in the sky!” and “Dream Big!”

Bill Mitchell’s affection for crisp, sharp lines (like a freshly pressed men’s suit) is evident with long smooth curves, crisp surface breaks, blended with sharp edges in the front and back. Even the windshield on the Monza GT has a crease down the center. (“Creased” glass wouldn’t arrive on a GM car until the 1967 Cadillac Eldorado and later the 1973 Chevy Monte Carlo and Pontiac Grand Prix) The curves and creases are so beautiful it’s easy to not notice that there’s no A-pillar! Now unless they were planning to use “transparent aluminum,” this was never going to happen in a production car. But, that’s what concept cars are all about. “Pie in the sky!” and “Dream Big!”

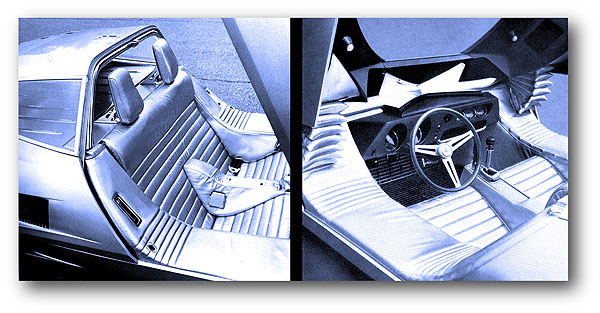

A close examination begs the question, “Where are the doors and how do you get into this thing?” Car designers of the time were still into the “jet age” theme of styling, with lots of “fighter jet” ideas – this was one of them. The idea here was “cockpit.” The entire roof section, wrap-around windshield, and sides (where the doors should be), was hinged forward and lifted up in one piece. You “stepped into the cockpit” and sat on a single, fixed bench seat with a padded center divider/console. The struts that held the top up were covered with accordion-like pleated covers that looked something from “Forbidden Planet.” The gas, brake, and clutch pedals were adjustable. The dash had a tach and speedometer, and the console gauges were angled towards the driver. The steering wheel looked a lot like what we would later see on the ’63 Corvette.

To access the engine and four-speed transaxle, the entire back of the car was hinged from just behind the rear wheels and tilted back – just like an exotic European sports car. The rear window had adjustable louvers, a styling element that was later seen on the Mako Shark-II. The back-end styling angled forward and was scooped in with Sting Ray-like dual taillight clusters. This back end shape later influenced the 1965-1969 Corvairs. The fiberglass body was reinforced with plastic panels and since there was no structural B-pillar, there was a built-in roll bar, just like a racecar.

The Monza GT was a startlingly little car. The Monza GT had a 92-inch wheelbase, was 162-inches in length (13.3-inches shorter than the Sting Ray) and 42-inches in height – 7.8-inches shorter than the Sting Ray. And now, lets address the ugly part – the headlights. They hadn’t yet figured out the flip-up or the flip-around style hidden headlights. Instead they designed what they called the “alligator-style” that had the upper and lower doors that split open at the forward leading edge. As beautiful as the car was, the exposed headlights are that bad.

The Monza GT was a startlingly little car. The Monza GT had a 92-inch wheelbase, was 162-inches in length (13.3-inches shorter than the Sting Ray) and 42-inches in height – 7.8-inches shorter than the Sting Ray. And now, lets address the ugly part – the headlights. They hadn’t yet figured out the flip-up or the flip-around style hidden headlights. Instead they designed what they called the “alligator-style” that had the upper and lower doors that split open at the forward leading edge. As beautiful as the car was, the exposed headlights are that bad.

What Chevrolet had was a Detroit-based, Porsche 718 GTR Coupe, but with a better-looking body design. So, what happened? The car was never magazine road tested or developed; it was just a concept car. Roger Penske once drove the car and said that he liked it better than the then, current-day Porsche. But they say, “Timing is everything.” Fitting a small, Corvair-based, two-seater sports car into the Chevrolet line was not likely. After all, Chevy only sold 14,531 ’62 Corvettes, compared to 1,172,212 Bel Air cars.

So, from a bean counter’s perspective, that’s not much of a market and so how do you justify making another sports car that’s likely to be low-volume? Some have said the Monza GT “came close” to production, but “how close” could have been weeks, days, or hours. Perhaps they should have sold the concept to a kit car company.

And the designers at Chevrolet were not the only Detroit team that was thinking along the same line. Over at Ford, Lee Iacocca’s concepts team, the “Fairlane Group” created their own mid-engine, 2-seater sports car called, “Mustang I”, powered by a German Ford Cardinal 1500-cc 60-degree V4 engine! At the United States Grand Prix in Watkins Glen, New York on October 7, 1962 Formula One driver Dan Gurney drove the Mustang I to a top speed of 120-mph! But just like the Monza GT and its sister, the “rear-engine” (Corvair-like) Monza SS Roadster, the Mustang I went nowhere. That’s typically what happens to concept cars.

But when Ford unleashed the Mustang and started the “Pony Car Wars,” a pint-sized Corvette didn’t stand a chance. The same thing happened to the Monza GT-inspired ’64 Pontiac Banshee, which looks even more like a C3 Corvette. Eventually the Monza GT “theme” was picked up by Opel, re-styled by Erhard Schnell, and produced as the Opel GT from 1968 to 1973.

The Monza SS was similarly styled, but in an open roadster configuration, different proportions, and no top what so ever. Unlike the GT, the SS was closer to its Corvair roots with a rear-engine layout. Both cars toured the car show circuit for several years. After the C3 Corvettes came out, the Monza GT and SS were pretty much put away.

The Monza SS was similarly styled, but in an open roadster configuration, different proportions, and no top what so ever. Unlike the GT, the SS was closer to its Corvair roots with a rear-engine layout. Both cars toured the car show circuit for several years. After the C3 Corvettes came out, the Monza GT and SS were pretty much put away.

The good news is that the Monza GT and the Monza SS survive and are now part of the GM Heritage Collection of cars that are parsed out to special car events. If you ever see one at a show, you’ll be surprised at how small they are. With all the body panels open, the cars look more like mail order kit cars, with no safety protection what so ever! A driver probably would not survive a 60-mph crash.

While the Monza GT “car” never arrived in Chevy dealer showrooms, it is obvious that if there hadn’t been the Monza GT in 1962, there might not have been a Mako Shark-II in 1965. And if there had been no Mako Shark-II, what would the C3 have looked like? As we’ll see in later installments of this series, Corvette styling could have gone off in several different “un-Shark-like” design tangents.

In Chapter 38 of Karl Ludvigsen’s updated book, “CORVETTE: America’s Star Spangled Sports Car” on pages 524 and 525 there are photos of full-size clay models of Corvette styling proposals that are “interesting” and would have made for a cool Pontiac or Dodge. No, had it not been for the Monza GT, the entire “Shark” profile might not have happened!

But lets bench Race just a little. Here’s another possible path for the Monza GT concept…

But lets bench Race just a little. Here’s another possible path for the Monza GT concept…

· Enlarged by about 120-percent,

· Large enough to fit a big-block in place of the Corvair flat-six

· Monocoque construction,

· 4-wheel independent suspension,

· 4-wheel disc brakes,

· 15×8-inch Rally wheels,

· Pop-up headlights, real doors, real interior, lift-off roof panels, real bumpers, etc –

Now you’ve got yourself a for-real, mid-engine C3 Corvette! That’s an interesting notion to chew on as we wait for the 2019 mid-engine Zora Corvette. – Scott

Coming up Next! The History of Mid-Engine Corvettes, 1960 to C8: Part 2 – The 1964 AWD CERV-II – Duntov’s planned Ford GT40-Killer and Le Mans Champion.

You can rest Part 1 of this series on the History of Mid-Engine Corvettes, HERE!