The 1964 Corvette GS-II – Frank Winchell’s Mid-Engine Engineering (Racing) Study with Jim “Mr. Chaparral” Hall

Dateline: 3.6.18 – Images GM Archives – This article was originally published in the November 2016 issue of Vette Vues Magazine

Dateline: 3.6.18 – Images GM Archives – This article was originally published in the November 2016 issue of Vette Vues Magazine

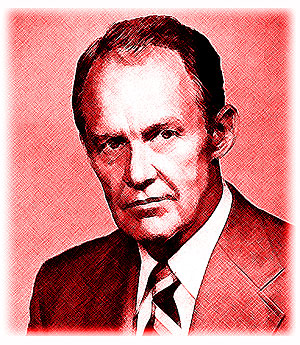

While Duntov lead the charge when it came to racing Corvettes, he wasn’t the only power player inside Chevrolet with a vision for a mid-engine Corvette. Frank Winchell was a low-profile company man who, unlike Duntov, did not like or seek out fame and attention. He was comfortable in his role as a corporate man. Winchell ran the Chevrolet R&D group from 1959 through 1966 and was a “take no prisoners,” “lets try it” kind of guy. While not a degreed engineer, he had a natural sense of how things worked and specialized in the design and development of automatic transmissions.

In Chapter 35 of Karl Ludvigsen’s 2014 edition of “CORVETTE – America’s Star Spangled Sports Car”, in Chapter 35, titled, “Winchell’s Raiders”, Karl shares that one of Winchell’s nicknames was, “General Bullmoose” after Al Capp’s Li’l Abner character, General Brashington T. Bullmoose, the cold-blooded capitalist tyrant tycoon. (This was obviously NOT a compliment) Chevrolet engineer and author of the book, “Chevrolet = Racing…? Fourteen Years of Raucous Silence!!, Paul Valkenburgh, said, “Winchell hated the phrase, ‘That can’t be done.’ Upon hearing that, there would be an inner explosion like a mine blast. He might grab an engineer by the lapels to bellow, ‘What that means is that you can’t do it. So, by God, I’ll find someone who can!’ And he usually did.”

It has been said that Duntov managed with love and enthusiasm, where as nobody worked “with” Frank Winchell – they worked “for” him. Frank was a tough “take no prisoners” kind of guy. So, it is no surprise that the two strong willed men had different ideas of what the Corvette should be. Duntov and Winchell respected each other, but they often locked horns. Winchell guided the designs of three unique mid-engine concept cars (the Monza GT, the GS-II, and the Astro II) and two rear-engine concept cars (the Monza SS and the XP-819), but because of his deliberate low profile as an engineer, he’s largely forgotten. However, he did have an interesting vision for what the Corvette “could be” within General Motors.

A bit of insight into Frank Winchell’s psyche can be found in a footnote on page 481 of the Ludvigsen’s book in a story from David E. Davis, former editor of Car and Driver and founder of “Automobile Magazine.” Davis once complimented Winchell when he told him that he deserved and should have a higher public profile. Winchell responded by saying, “You may be right, but I’m not like you. You’re so damn sure of yourself, you can talk to anybody. I walk into a room full of people and I fully expect everybody to turn around and say, ‘Who is that stupid sonovabitch that just walked in?’” Perhaps Winchell was self-conscious of his lack of engineering credentials.

Paul Valkenburgh also said, “… Winchell preferred to work under the radar. He preferred it that way. Frank was opposed to exposure. He wanted Chevy R&D to be invisible. Frank felt that the more visible he himself was, the less he could get away with. He had his own locked shop, separate from all other engineering activities, and it was almost totally self-sufficient. Even if they were invited, few other managers were comfortable in Frank’s world. One of his superiors made it a point to visit only when Frank was out of the building.”

Before all the bad publicity took the glow off of the Corvair, the car was considered “advanced engineering hardware.” The Corvair’s transaxle/swing axle rear suspension, while not dissimilar to what was used on Porsches and VWs, was heady hardware for R&D tinkerer types like Winchell and Duntov. Both men delighted in what could be done with the new addition to the Chevrolet parts bin. Winchell was also deeply involved in the engineering defense of the Corvair that resulted in the creation of GM’s famous, 67-acre Black Lake asphalt test facility.

Winchell’s Corvair activities and fascination with Porsche sports cars had a powerful impact on his thinking as to what the Corvette could become. These were the early, fluid days of the Corvette’s timeline when there were many factions inside Chevrolet that wanted the Corvette to be “something else.”

Winchell directed the construction of two cars using the Corvair’s flat-six engine and transaxle – the mid-engine Monza Coupe and the rear-engine Monza SS. Both beauties were styled by Larry Shinoda and looked like, “When can we buy one?” We covered the Monza GT in Part 2 of this series in the September 2016 issue of Vette Vues. While the notion of a Corvair engine powering a “Corvette” probably makes most Vette enthusiasts wince, it was indeed a mid-engine layout, and styled by Larry Shinoda, that was, in hindsight, obviously part of the “Mako Shark” family.

Winchell, the “let’s try it” engineer, wanted to take the mid-engine/transaxle layout to the next level with V8 power. Yes, now we’re talking! Frank recruited young engineer, Jim Musser, Jr. to work out the Monza GT and was pleased enough with Jim’s work to set him loose on a V8 version of the Monza GT’s design. Being a competitive, aggressive kind of guy, Winchell no doubt wanted to stick it in Duntov’s eye, so he named his mid-engine sports car “GS-II”’ an obvious jab at Duntov’s stillborn Grand Sport project.

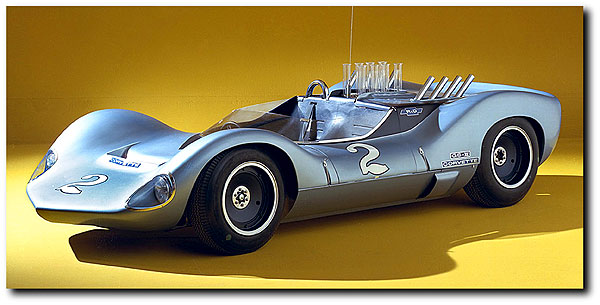

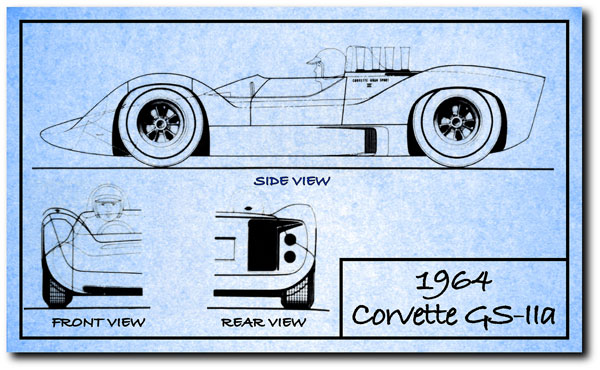

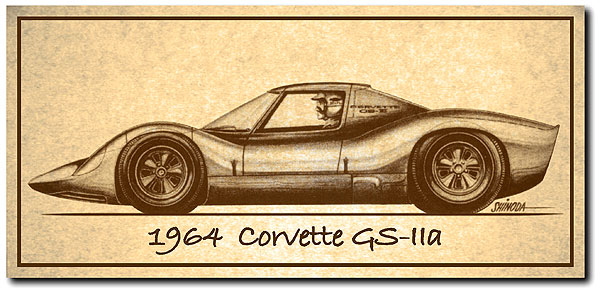

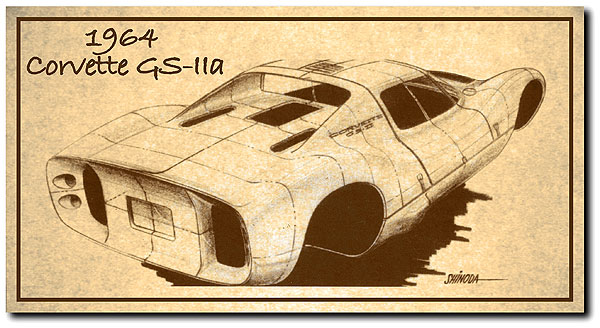

There were two GS II cars, GS-IIa and GS-IIb. Monocoque design and construction for racing sports cars was quickly replacing tube frame-type construction for advanced racecars. GS-IIa was built using a spot-welded, sheet steel tub, powered by an all-aluminum 327 small-block Chevy engine, with a torque converter, Weber carbs, and dragster-style zoomy headers. Winchell again drafted Larry Shinoda to design the body for a coupe and open roadster configuration. Of course, Shinoda’s cars looked like they were ready for the GM Futurama at the ’64-’65 World’s Fair! Stop for a moment and consider what regular cars looked like in 1964-1965.

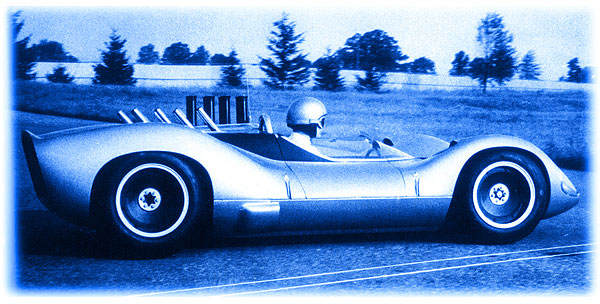

Winchell wanted his GS-II concept to be as light as possible, so in 1964 he built the GS IIb that had an aluminum monocoque tub, using the same fully independent suspension design with the largest wheels and tires available, 327 all-aluminum small-block, plus ultra thin body panels that were bonded with 3M adhesive and oven-cured. The completed car weighed in at just 1,450-pounds! There’s no record of how much horsepower the engine made, but 400-to-425-hp would be a reasonable guestimate. How fast was the GS-IIb you wonder? Winchell’s little mid-engine rocket blasted GM’s Milford Proving Grounds at 198-mph!

Winchell’s bigger picture plan called for the initial construction of 500 GS-II Coupes, with gull-wing doors to be used as street and track cars. The proposal sounds a lot like Duntov’s plan to built 1,000 Grand Sport Corvettes to be sold through Chevrolet dealerships. But Winchell had an interesting larger vision – that of a “family of Corvettes.” Imagine, regular production Corvette Sting Rays, along with the lightweight Grand Sport Corvettes, then the super-light GS-II Corvettes; all available from your friendly, local Chevrolet dealer. Perhaps Winchell should have proposed breaking the Corvette off into its own division within GM. There would have even been a place for a Thunderbird-killer, four-seater Sting Ray. But we all know that this would never happen. In stead, Winchell let the grand standing Duntov take the heat for the Grand Sport. So, no Grand Sport, no GS-II, and thankfully, no four-seater Sting Ray.

You can’t blast around the Milford Proving Grounds at nearly 200-mph without attracting attention, which is exactly what Winchell was opposed to. But, being a resourceful guy, Frank found a way around. In a 2001 interview with Jim Hall and Brian Redman, by writer Paul Hanley, we learned that

Winchell had heard about the racing exploits of young Texas oilman Jim Hall, and invited Hall to the Cornell Labs to fly the B-24 variable stability airplane. The two men with a passion for engineering, (Hall had an engineering degree from Cal Tech) and hit it off right away. Winchell hired the services of Jim Hall and his ultra-private Rattle Snake Raceway in Midland, Texas for further R&D work on the GS-II concept – far, far away from the prying eyes of the automotive press and GM’s brass. Winchell and Hall helped bring engineering/development instrumentation to racecar building.

While Winchell envisioned street versions of the GS-II, the actual steel and later aluminum monocoque GS-II cars were pure R&D project cars – another of Winchell’s “let’s see” engineering studies. With the GS-II dead in the water, the car became an extension of Hall’s Chaparral series of racecars. Winchell and Chevrolet weren’t designing Hall’s Chaparrals, and Hall wasn’t doing development work on a production version of the GS-II. The juncture of the two men was mutually functional; Winchell wanted a private place to thrash out new structure/suspension development, and Hall got help making unique parts that he and his team could not produce. According to the Paul Haney/Hall/Redman interview, Winchell would often tell Hall, “Let me make one of those, I know how to do that.”

Prototype racing sports cars were developing at an astonishing rate and it wasn’t long before the GS-IIb-based cars were eclipsed by new and improved designs. What became of the GS-IIa and GS-IIb is not known to the best of my research and information. Since these were R&D cars, after they outlived their usefulness, they were most likely disposed of. Yes, another piece of Corvette history that ultimately ended up as scrap. They couldn’t keep everything, I suppose.

This was a very heady time, and Frank Winchell’s GS-II experimental Corvette played an important part in the long story of the mid-engine Corvette that is still developing. We will cover Winchell’s third mid-engine “Corvette” the XP-819 next month in Part 5 and then Winchell’s “Astro II” concept in Part 7 of our series. The XP-819 (currently undergoing a total restoration) was a pure engineering study that miraculously survived, in pieces under a tarp at Smokey Yunick’s “Best Damn Garage in Town.” But the 1968 Astro II looked like it was ready for production!

Special thanks to authors Paul Valkenburgh, Karl Ludvigsen and Paul Haney for their insights into the interesting personalities of Frank Winchell and Jim Hall. – Scott

Coming up Next! Part 5 of 16, The 1964 XP-819 “Rear-Engine” Engineering Study