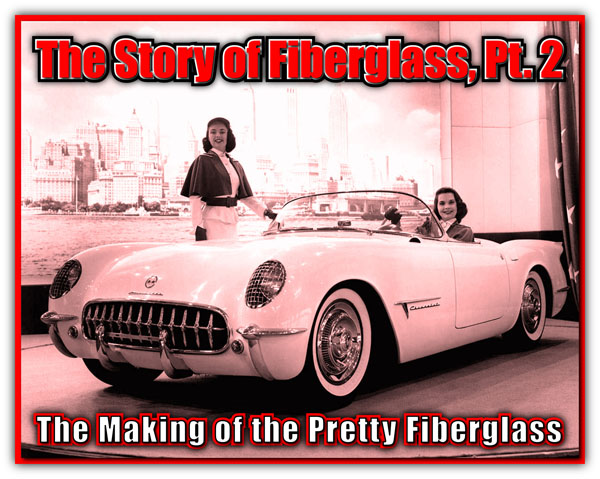

NOTE: This story was first published in the January 2023 issue of Vette Vues Magazine – We left “The Story of Fiberglass” in the October 2022 issue of Vette Vues. The story goes back to 1880 when Herman Hammesfahr, a Prussian-American scientist, was issued the first-ever U.S. Patent for “glass fibers”. Self-taught “scientists” had been playing with making glass fibers long before 1880. But for decades, many said, “… interesting stuff, but what do you do with it?”

Once the Patent was issued, it took sixty years before the answer to that question was discovered. One of the earliest applications was for the military’s new radar systems during WW II. As microwave energy passes right through fiberglass, large globes were made to house the spinning radar units that gave the Allies the edge during the war.

Post-war, industries that were part of the war effort just wanted to get back to commercial business. The selling of fiberglass (GRP – glass-reinforced plastic) into the automobile industry was very difficult. The industry just couldn’t see it. After all, car parts have always been metal. It took small-time entrepreneurs to show, “Look what we can do with this stuff!”

The “First” Fiberglass Car

After the war, in 1946, Bill Tritt, from Pasadena, California applied what he’s learned while working at Douglas Aircraft to build fiberglass-hulled 21-foot sloop pleasure boats. Because of his hands-on expertise, U.S. Air Force Major Kenneth Brooks commissioned Tritt to build a fiberglass body for his wife’s personal Jeep. Major Brooks was so happy with his re-bodied Jeep he commissioned Tritt to build a slick fiberglass body for a sports car.

As the car was being built, Eric Irwin, from Costa Mesa was inspired to build a similar sports car that became the Lancer sports car. When Mrs. Brooks car was completed, she called the car the “Brooks Boxer” because she loved boxed dogs. In 1950 Tritt teamed with Otto Baeyer to form the Glasspar Company to expand the boat hull business.

As the car was being built, Eric Irwin, from Costa Mesa was inspired to build a similar sports car that became the Lancer sports car. When Mrs. Brooks car was completed, she called the car the “Brooks Boxer” because she loved boxed dogs. In 1950 Tritt teamed with Otto Baeyer to form the Glasspar Company to expand the boat hull business.

Enter the Naugatuck Chemical Company. Their business wasn’t just chemicals, they wanted to be part of what growing numbers of visionaries saw fiberglass as a modern marvel of wartime technology. Several companies had tried to get Detroit to embrace the new material but weren’t having any luck. The car industry needed to see a real fiberglass “car”. Naugatuck was given a license to make replicas of the Brooks Boxer and a version for themselves. This one had opening doors and was called “Alembic-I”.

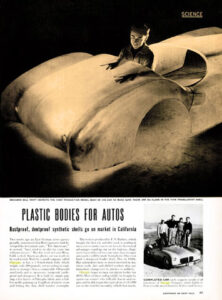

In the 1950s and 1960s Life Magazine was one of the most popular magazines in America. Bill Tritt from the Glasspar Company built the Alembic-I and was featured in a one-page article on Life’s “Science” page, titled, “Plastic Bodies For Autos.” The photo in the magazine was fascinating, showing the translucent quality of fiberglass with Tritt’s hands on the underside of the rear deck of a sports car body that Glasspar was selling for $600, equal to $6,747 in today’s dollars. The following month, the Alembic-I was on display at Philadelphia’s National Plastics Exposition, on March 11, 1952. Seen as part of the war dividend, fiberglass was as futuristic, gee-wiz stuff!

In the 1950s and 1960s Life Magazine was one of the most popular magazines in America. Bill Tritt from the Glasspar Company built the Alembic-I and was featured in a one-page article on Life’s “Science” page, titled, “Plastic Bodies For Autos.” The photo in the magazine was fascinating, showing the translucent quality of fiberglass with Tritt’s hands on the underside of the rear deck of a sports car body that Glasspar was selling for $600, equal to $6,747 in today’s dollars. The following month, the Alembic-I was on display at Philadelphia’s National Plastics Exposition, on March 11, 1952. Seen as part of the war dividend, fiberglass was as futuristic, gee-wiz stuff!

The Alembic-I was a drivable car and definitely got the attention of General Motors, a major American industrial giant with a passion for advanced technology. Their Hydra-Matic automatic transmission was first seen on the road in the 1937 Buick and used during the war in the M5 Stewart tank, which would revolutionize the auto industry. The development of automatic transmissions was viewed as a safety feature and enabled more women to drive cars.

The Alembic-I was a drivable car and definitely got the attention of General Motors, a major American industrial giant with a passion for advanced technology. Their Hydra-Matic automatic transmission was first seen on the road in the 1937 Buick and used during the war in the M5 Stewart tank, which would revolutionize the auto industry. The development of automatic transmissions was viewed as a safety feature and enabled more women to drive cars.

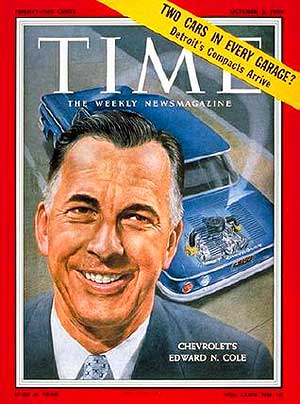

In 1949 GM pioneered the mass-produced overhead-valve Cadillac and Oldsmobile engine, a major departure from flat-head engine design. Ed Cole was instrumental in the OHV project and when he was moved to Chevrolet’s Chief of Engineering, started work on the simpler Chevy version that became the small-block Chevy. So, this new glass-reinforced plastic “fiberglass” material was a tasty plum for the technology-hungry GM!

In 1949 GM pioneered the mass-produced overhead-valve Cadillac and Oldsmobile engine, a major departure from flat-head engine design. Ed Cole was instrumental in the OHV project and when he was moved to Chevrolet’s Chief of Engineering, started work on the simpler Chevy version that became the small-block Chevy. So, this new glass-reinforced plastic “fiberglass” material was a tasty plum for the technology-hungry GM!

GM Takes the Bait!

A team of GM engineers was dispatched to Naugatuck to learn all they could from Ebers and Tritt about the new plastic material. Designers and stylists immediately saw GRP as an easy way to create complex concept car bodies to market test new ideas at a fraction of the cost of making metal-bodied concept cars. While all this was going on, Harley Earl and his design team were busy developing Earl’s vision of a “Chevy sports car” with the name, “Project Opel.”

While it is true that the Corvette was the brain-child of Harley Earl, he didn’t actually “draw out” what became the Corvette Motorama car. That credit goes to Earl’s design team, assigned to make a beautiful GRP body for the chassis layout that engineer and industrial designer Robert McLean created. Draftsman Carl Peebles and assistant Bill Bloch put pencil to paper to create the shape Earl directed. Engineer Vincent Kaptur worked out the body’s engineering, and stylists Carl Renner, Bill Bloch, and clay modelers, Tony Balthasar and Julius “Scotty” Teitlebom sculpted Earl’s design.

While it is true that the Corvette was the brain-child of Harley Earl, he didn’t actually “draw out” what became the Corvette Motorama car. That credit goes to Earl’s design team, assigned to make a beautiful GRP body for the chassis layout that engineer and industrial designer Robert McLean created. Draftsman Carl Peebles and assistant Bill Bloch put pencil to paper to create the shape Earl directed. Engineer Vincent Kaptur worked out the body’s engineering, and stylists Carl Renner, Bill Bloch, and clay modelers, Tony Balthasar and Julius “Scotty” Teitlebom sculpted Earl’s design.

The plaster model was completed in April 1952 and went on display in GM’s Private Viewing Auditorium, where it received rave reviews from the GM executives. In May 1952, Ed Cole was promoted to Chevrolet Chief of Engineering and was brought into the new sports car project.

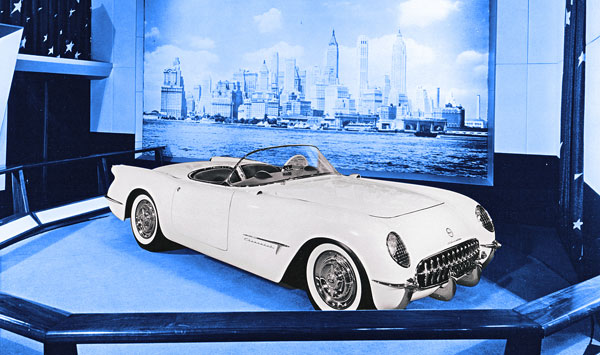

On June 2, 1952, Harley Earl made his formal pitch to GM’s president, Charles Wilson, and Chevrolet General Manager, Thomas Keating, and quickly received approval for the construction of a prototype concept car for the 1953 GM Motorama, in New York City. The car’s code name was “Opel Sports Car”. This gave the design and fabrication team just seven months to crank out a winner, and did they ever!

On June 2, 1952, Harley Earl made his formal pitch to GM’s president, Charles Wilson, and Chevrolet General Manager, Thomas Keating, and quickly received approval for the construction of a prototype concept car for the 1953 GM Motorama, in New York City. The car’s code name was “Opel Sports Car”. This gave the design and fabrication team just seven months to crank out a winner, and did they ever!

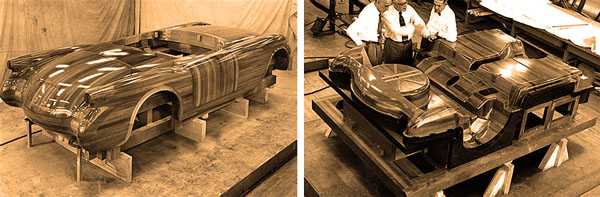

Work orders were issued on July 3, 1952, for the construction of two Motorama bodies; one for promotion and one for testing. Preliminary chassis designs were initiated the previous spring and the body shape had already been finalized. All they had to do was make Project Opel a real, running car.

Work orders were issued on July 3, 1952, for the construction of two Motorama bodies; one for promotion and one for testing. Preliminary chassis designs were initiated the previous spring and the body shape had already been finalized. All they had to do was make Project Opel a real, running car.

In September 1952, just four months before the January Motorama Show, Chevrolet’s Parts Fabrication Department was directed to design and build fiberglass bodies. All of the manufacturing specifics had to be worked out; how many pieces needed to be made? Then molds are produced and how will the pieces fit together bonding or bolting? Where will the attachment points be located and how will the castings be groomed and finished? Dozens and dozens of concerns had to be considered.

In September 1952, just four months before the January Motorama Show, Chevrolet’s Parts Fabrication Department was directed to design and build fiberglass bodies. All of the manufacturing specifics had to be worked out; how many pieces needed to be made? Then molds are produced and how will the pieces fit together bonding or bolting? Where will the attachment points be located and how will the castings be groomed and finished? Dozens and dozens of concerns had to be considered.

Unlike the one-of-a-kind Brooks Boxer and Alembic-I, the body had to be engineered for mass production. The directive was to lay out the body parts as if they were steel, which makes sense, as that’s what they were used to doing. Besides, fiberglass was the quick way to get to a body design that would later be made from steel. This was the plan at the time.

Also in the same month, the “Project Opel” name was dropped in favor of “Corvette”. The word “corvette” is a term that dates back to the 1650s for armed naval warships smaller than a frigate; and used for coastal patrols, fighting minor wars, and supporting large fleets. The heavily masted small ships were quick and maneuverable. Corvette naval ships are still built today.

Also in the same month, the “Project Opel” name was dropped in favor of “Corvette”. The word “corvette” is a term that dates back to the 1650s for armed naval warships smaller than a frigate; and used for coastal patrols, fighting minor wars, and supporting large fleets. The heavily masted small ships were quick and maneuverable. Corvette naval ships are still built today.

By November parts were completed for 30 major and 32 minor components with a total combined weight of 340 pounds, nearly 2/3rds the estimated weight of a similar steel body. The completed body with metal supports and bracing, ready to mount on the chassis, weighed 411 pounds. On December 10, 1952, the already designed chassis was completed, and on December 12, 1952, the first of two Motorama bodies were completed.

With all the parts ready for assembly, the first Motorama Corvette was completed on December 22, 1952, a little more than two weeks before the New York City Motorama, held at the Waldorf-Astoria. The cost of the two Motorama Corvettes was $60,000 in January 1953. In 2022 dollars adjusted for inflation, the number inflates to $672,000!

With all the parts ready for assembly, the first Motorama Corvette was completed on December 22, 1952, a little more than two weeks before the New York City Motorama, held at the Waldorf-Astoria. The cost of the two Motorama Corvettes was $60,000 in January 1953. In 2022 dollars adjusted for inflation, the number inflates to $672,000!

Earl and his team hit it out of the park!

The Corvette was a smash hit, and GM, wanting to take a technological leadership position, quickly ordered the car into full-scale production as a 1953 model, with the fiberglass body as a temporary material. Thousands saw Harley Earl’s vision of a Chevy sports car and wanted one immediately. Arguably the most important citizen to see the Motorama Corvettes was a Russian-Belgian engineer looking for a job with a big Detroit car company; Zora Arkus-Duntov.

The Corvette was a smash hit, and GM, wanting to take a technological leadership position, quickly ordered the car into full-scale production as a 1953 model, with the fiberglass body as a temporary material. Thousands saw Harley Earl’s vision of a Chevy sports car and wanted one immediately. Arguably the most important citizen to see the Motorama Corvettes was a Russian-Belgian engineer looking for a job with a big Detroit car company; Zora Arkus-Duntov.

Zora was a push-over for pretty girls and a charming lady’s-man. Years later, Zora said that when he first saw the Corvette he thought it was the most beautiful car he’d ever seen and immediately decided that he wanted to be part of Corvette. Chevrolet’s Chief engineer Ed Cole was building his crack Corvette team and had already hired three-time Indy 500 winner and automotive engineer, Mauri Rose. Duntov’s official start date with GM was May 1, 1953.

Zora was a push-over for pretty girls and a charming lady’s-man. Years later, Zora said that when he first saw the Corvette he thought it was the most beautiful car he’d ever seen and immediately decided that he wanted to be part of Corvette. Chevrolet’s Chief engineer Ed Cole was building his crack Corvette team and had already hired three-time Indy 500 winner and automotive engineer, Mauri Rose. Duntov’s official start date with GM was May 1, 1953.

Building a one-off concept car, such as the Brooks Boxer and the Alembic-I, or two show cars is one thing; making a new unproven concept with a totally new body material for mass production is a whole other thing. At this point, fiberglass was the perfect material to launch such an adventure. Initial molds were already completed, they just needed more of them. There simply wasn’t enough time to make steel stamping tools for steel bodies. However, plans were being made to make the Corvette a steel-bodied car for the 1954 model.

Building a one-off concept car, such as the Brooks Boxer and the Alembic-I, or two show cars is one thing; making a new unproven concept with a totally new body material for mass production is a whole other thing. At this point, fiberglass was the perfect material to launch such an adventure. Initial molds were already completed, they just needed more of them. There simply wasn’t enough time to make steel stamping tools for steel bodies. However, plans were being made to make the Corvette a steel-bodied car for the 1954 model.

GM wanted to strike while the demand for a production Corvette was hot. Completed fiberglass 1953 Corvettes started rolling off the temporary Flint Michigan assembly plant on June 29, 1952, and the 300th 1953 Corvette was completed on December 24, 1953. The list price for the first Corvette was $3,498 and there were two options; the heater cost $91 and the AM radio cost $145, for a total price for the “loaded” Corvette of $3,734, or $41,521 in 2022 dollars. And snap-up plastic side windows were standard, no glass windows!

GM wanted to strike while the demand for a production Corvette was hot. Completed fiberglass 1953 Corvettes started rolling off the temporary Flint Michigan assembly plant on June 29, 1952, and the 300th 1953 Corvette was completed on December 24, 1953. The list price for the first Corvette was $3,498 and there were two options; the heater cost $91 and the AM radio cost $145, for a total price for the “loaded” Corvette of $3,734, or $41,521 in 2022 dollars. And snap-up plastic side windows were standard, no glass windows!

For comparison, a 1953 Chevy Bel Air Hardtop Coupe listed for $2,051. A 1953 Cadillac Coupe de Ville Hardtop Coupe listed for $3,995 and a 1953 Lincoln Cosmopolitan Sport Coupe listed for $3,625. The Corvette’s total lack of refinements and nosebleed price seemed like a joke to the public.

For comparison, a 1953 Chevy Bel Air Hardtop Coupe listed for $2,051. A 1953 Cadillac Coupe de Ville Hardtop Coupe listed for $3,995 and a 1953 Lincoln Cosmopolitan Sport Coupe listed for $3,625. The Corvette’s total lack of refinements and nosebleed price seemed like a joke to the public.

Ed Cole Gets a Wet Surprise

But what about “the car”? Unfortunately, few were impressed. Chevrolet Chief Engineer, Ed Cole, had the honor of driving one of the first Corvettes on a weekend jaunt. Cole’s honor quickly turned to horror when it rained for most of the weekend and the Corvette leaked water everywhere. The foot-wells quickly looked like the bilge of a ship with water sloshing everywhere. Even the inside of the doors were holding water. The leaking issue was quickly fixed, but the car was still crude, especially considering the price.

But what about “the car”? Unfortunately, few were impressed. Chevrolet Chief Engineer, Ed Cole, had the honor of driving one of the first Corvettes on a weekend jaunt. Cole’s honor quickly turned to horror when it rained for most of the weekend and the Corvette leaked water everywhere. The foot-wells quickly looked like the bilge of a ship with water sloshing everywhere. Even the inside of the doors were holding water. The leaking issue was quickly fixed, but the car was still crude, especially considering the price.

LOTS of Hand Labor

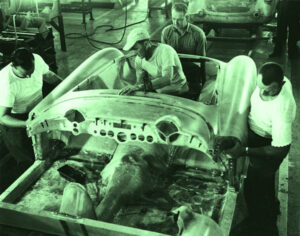

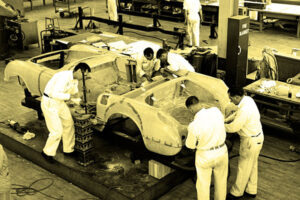

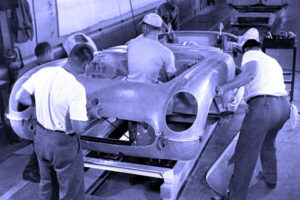

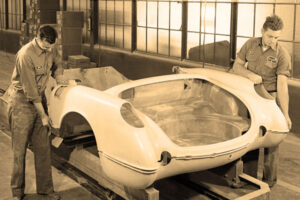

While making bodies from GRP was much less expensive than making steel stamping tools, the hand labor was extensive. All of the 62 fiberglass parts required careful trimming, filing, and sanding. Various pieces had to be bonded (“glued”, same as a plastic model car kit) and groomed to fit. Two-hundred mounting holes had to be drilled for each body.

While making bodies from GRP was much less expensive than making steel stamping tools, the hand labor was extensive. All of the 62 fiberglass parts required careful trimming, filing, and sanding. Various pieces had to be bonded (“glued”, same as a plastic model car kit) and groomed to fit. Two-hundred mounting holes had to be drilled for each body.

After the assembled bodies were painted, tiny air bubbles surfaced after the body spent time in the 300-degree paint-curing ovens. All of the imperfections have to be repaired and the bodies repainted. If you look carefully at the workers you clearly see that no one was using any kind of protection while filing, sanding, drilling, and painting the fiberglass; which is incredible from today’s perspective!

After the assembled bodies were painted, tiny air bubbles surfaced after the body spent time in the 300-degree paint-curing ovens. All of the imperfections have to be repaired and the bodies repainted. If you look carefully at the workers you clearly see that no one was using any kind of protection while filing, sanding, drilling, and painting the fiberglass; which is incredible from today’s perspective!

Most of the 300 Corvettes were gifted to GM executives, politicians, and movie star John Wayne, who quickly discovered that his 6′ – 4” frame was too big for the car. (The Duke was a fan of big Pontiac stations!) International sportsman Briggs “Swift” Cunningham bought a Corvette for his wife.

Most of the 300 Corvettes were gifted to GM executives, politicians, and movie star John Wayne, who quickly discovered that his 6′ – 4” frame was too big for the car. (The Duke was a fan of big Pontiac stations!) International sportsman Briggs “Swift” Cunningham bought a Corvette for his wife.

Not Ready For Prime Time

The initial batch of Corvettes sold as 1953 models should have been used as pilot cars, as they were seriously not ready for prime-time. As the 1953 Corvettes were being built in Flint, the full might of the GM St. Louis assembly plant was being readied for serious mass production of 10,000 Corvettes for 1954. While the Motorama debut was a home run, the production cars were a strikeout.

The initial batch of Corvettes sold as 1953 models should have been used as pilot cars, as they were seriously not ready for prime-time. As the 1953 Corvettes were being built in Flint, the full might of the GM St. Louis assembly plant was being readied for serious mass production of 10,000 Corvettes for 1954. While the Motorama debut was a home run, the production cars were a strikeout.

In hindsight, it was a good thing Chevrolet did not put off the Corvette until 1954 to go with the steel body. As reviews started coming in for the 1953 Corvette and stories circulated about the car’s underwhelming performance, fit, and finish, interest quickly diminished. By the end of the 1954 production run, only 3,650 Corvettes were ordered, way off the 10,000 projected units.

In hindsight, it was a good thing Chevrolet did not put off the Corvette until 1954 to go with the steel body. As reviews started coming in for the 1953 Corvette and stories circulated about the car’s underwhelming performance, fit, and finish, interest quickly diminished. By the end of the 1954 production run, only 3,650 Corvettes were ordered, way off the 10,000 projected units.

The public did not yet grasp the sports car concept and took a major chill to Chevy’s sports car, so much so that only 700 1955 Corvettes were sold! The new 265 small block didn’t help. If Chevrolet had gone with a steel body, with those kinds of reviews, and sales, they would have immediately killed the Corvette.

Something had to be done to shake off the car’s bad start, so Harley Earl restyled the car for 1956 and by that time Cole, Duntov, Rose, and others started fielding racing versions of the Corvette to give the car a shot in the arm of “Corvette vitamin C”. Their efforts paid off and that’s the next chapter of the Corvette story.

Something had to be done to shake off the car’s bad start, so Harley Earl restyled the car for 1956 and by that time Cole, Duntov, Rose, and others started fielding racing versions of the Corvette to give the car a shot in the arm of “Corvette vitamin C”. Their efforts paid off and that’s the next chapter of the Corvette story.

Other GM Division Wanted Their Own “Corvette”

The dynamic 1953 Motorama Corvette, with its sexy, hi-tech “fiberglass plastic” body seriously got the attention of GM’s other car divisions; Pontiac, Buick, and Oldsmobile. When the doors to the 1954 GM Motorama event opened, the other GM divisions had their version of the Corvette. But by then, it was just a dog-and-pony show. The Pontiac Bonneville Special, the Buick Wild Cat-II, and the Oldsmobile F-88 were clearly take-offs of the svelte Corvette. Pontiac, Buick, and Oldsmobile essentially told Chevrolet, “The Corvette is all yours, Chevy!”

The dynamic 1953 Motorama Corvette, with its sexy, hi-tech “fiberglass plastic” body seriously got the attention of GM’s other car divisions; Pontiac, Buick, and Oldsmobile. When the doors to the 1954 GM Motorama event opened, the other GM divisions had their version of the Corvette. But by then, it was just a dog-and-pony show. The Pontiac Bonneville Special, the Buick Wild Cat-II, and the Oldsmobile F-88 were clearly take-offs of the svelte Corvette. Pontiac, Buick, and Oldsmobile essentially told Chevrolet, “The Corvette is all yours, Chevy!”

In recent years, some writers, having recently discovered those other GM Motorama cars have concluded, “What was Chevy thinking? These cars would have clobbered the Corvette!” Not so. Each car was over-designed, slathered with chrome, powered by big V8s, and dripping with futuristic features that would have pushed their price to hyper-expensive Cadillac Eldorado territory.

In recent years, some writers, having recently discovered those other GM Motorama cars have concluded, “What was Chevy thinking? These cars would have clobbered the Corvette!” Not so. Each car was over-designed, slathered with chrome, powered by big V8s, and dripping with futuristic features that would have pushed their price to hyper-expensive Cadillac Eldorado territory.

Meanwhile, in Dearborn, Ford’s 1955 Thunderbird, loaded with creature comforts, a steel body, V8, and priced similar to the Corvette, vastly outsold Chevy’s plastic car. But Ford didn’t seriously believe in the two-seater T-Bird. As the first Thunderbirds were hitting showrooms, Ford was busy designing the four-seater ’58 T-Bird replacement. The American “sports car” was still an unproven concept.

Meanwhile, in Dearborn, Ford’s 1955 Thunderbird, loaded with creature comforts, a steel body, V8, and priced similar to the Corvette, vastly outsold Chevy’s plastic car. But Ford didn’t seriously believe in the two-seater T-Bird. As the first Thunderbirds were hitting showrooms, Ford was busy designing the four-seater ’58 T-Bird replacement. The American “sports car” was still an unproven concept.

So what saved the Corvette from certain oblivion? Racing!

Over the decades, many inside GM couldn’t understand the Corvette and wanted to morph it into a regular car (the experimental four-seater 1963 Sting Ray) or better yet, gone! While the Corvette’s fortunes began to slowly turn around with the introduction of the 265 V8 small-block Chevy in 1955 and an all-new body for 1956, it was racing that saved the Corvette. Were it not for racing, the Corvette never would have made it into the 1960s.

Over the decades, many inside GM couldn’t understand the Corvette and wanted to morph it into a regular car (the experimental four-seater 1963 Sting Ray) or better yet, gone! While the Corvette’s fortunes began to slowly turn around with the introduction of the 265 V8 small-block Chevy in 1955 and an all-new body for 1956, it was racing that saved the Corvette. Were it not for racing, the Corvette never would have made it into the 1960s.

Corvette was the most unlikely of all possible cars for a major car manufacturer the likes of “gray suit” GM to make. Within major corporations, unusual projects need what are called, “corporate angels”. These are power players with the authority to do unusual or covert projects.

Corvette was the most unlikely of all possible cars for a major car manufacturer the likes of “gray suit” GM to make. Within major corporations, unusual projects need what are called, “corporate angels”. These are power players with the authority to do unusual or covert projects.

Corvette’s leading corporate angels were Harley Earl and Ed Cole and followed by Bill Mitchell, Zora Arkus-Duntov, and Mauri Rose. They all had “gasoline in their veins” and were essential to the survival of the Corvette. From the perspective of 1953-1954, it was impossible to see that one day in the future, the Corvette would become one of GM’s top technology flagships and Detroit’s ultimate success story. –Scott

![]()