A look back at Chevrolet’s experimental, prototype, concept car, and show car Corvettes

words and art by Scott Teeters, written for Vette magazine as republished from SuperChevy.com Read the other experimental stories HERE.

General Motors makes hundreds of kinds of cars and trucks. Some sell hundreds of thousands of units a year, which makes Chevrolet’s Corvette a complete enigma. Given the small number of Corvettes sold every year, it is a modern American manufacturing miracle that the car survived for 61 years.

The Corvette was “officially” born on January 17, 1953 at the GM Motorama Show at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel, in New York. To understand the impact of Harley Earl’s two-seater sports car concept car, you have to look at typical cars of 1953. The car was low and sleek, and wasn’t over festooned with styling gimmicks. Based on the response from attendees, Chevrolet rushed the car into production, and the rest is history.

Today, the Corvette is GM’s flagship car. When Chevrolet unleashes a new Corvette, the automotive world stops to take notice. But things were not always this way. Up to the C4, there were many inside GM that wanted to see the Corvette go away. For the first 20-some years, the car suffered from an identity crisis. Inside GM there were always those that wanted the Corvette to be something different; a lightweight sports car, a mid-engine car, a rear-engine car, a four-seater personal luxury car, powered by a boxer-type flat-six, Wankel rotary-powered, turbocharged small-displacement hemi-headed double-overhead cam powered, and even an all-aluminum car. Chevrolet kept the loyal faithful stoked with two or three experimental, prototype, show car Corvettes per year. From an enthusiast’s perspective, this was endlessly fascinating.

This is part seven of a chronological look back at Chevrolet’s high-profile experimental, prototype, concept car, and show car Corvettes. Some of the cars had exotic names such as, “Astro-I,” “Astrovette” and “Geneve.” Others had experimental prototype numbers, such as “XP-700” and “XP-882.” And some had sexy names, such as, “Nomad,” “Mulsanne,” “Snake Skinner,” “Mako Shark,“ and “Tiger Shark.” In retrospect, a few of the cars were the shape of things to come, but most were simply, “Here’s an idea of something we’re working on.” Either way, it was all a ton of fun!

1964 World’s Fair Corvette

It was post JFK assassination America, the Beatles had arrived, and anticipation for the 1964-1965 New York World’s Fair was over-the-top. This was corporate America’s chance to show off their goods, as well as present their vision of “The Future.” The biggest attraction was the GM Futurama. Inside the exhibit, visitors viewed scale models and a multi-media show of GM’s vision for the “near future.” Part of the window dressing for GM’s vision of the future was the Stiletto concept car and a bright red, dressed up ’64 Corvette Sting Ray coupe.

The Corvette already looked like a car from another planet, so the Chevrolet Styling Department had lots of fun with this one. In 1964, Corvette buyers had the choice of a coupe or roadster, a variety of engines, manual or automatic transmission, an assortment of extras, and color options. Today, dealerships are boutiques where you can trick out your Corvette with a staggering amount of options. If Chevrolet had the boutique model back in 1964, a Corvette similar to this might have been available.

There were three major features on the World’s Fair Corvette that just screamed out. First was the deep, 16-coat, candy apple red paint that accentuated the beautiful curves, creases, and humps of the Sting Ray. Next was the unique side-pipes treatment. Bill Mitchell, GM’s Chief of Styling loved side-pipes, that’s why nearly every Corvette show and concept car had them. Actually, what was on the show car were non-functioning plastic mockups. The public didn’t know that side-pipes would soon be an option on the ’65 Corvette. And lastly, there was something very interesting happening on the smooth ’65-’67 hood—the chromed fuel-injection plenum chamber cover was poking through the hood! It only took 45 years for the “peekaboo” hood treatment to show up on the ’09 ZR1. This was no mocked-up, non-functioning feature, either. A special, tall fuelie unit was created to achieve the effect. Of course, the fuelie was on its way out, to be replaced with the Mark IV big-block, but this would have been a very cool option.

The car was very close to a production version, but dripping with extras. Brakes were upgraded to ’65 four-wheel discs and up front the egg-crate grille would later show up on the ’67 Corvette. The production interior air vent on the B-pillar was replaced with a forward-facing, mesh-covered scoop. On the rear deck, stylists added two elliptical air vents, similar to those of the 1959 Stingray Racer. Completing the exterior, two extra taillights were added. Under the hood, the L84 engine was painted black and dressed up with chrome valve covers, fan, ignition shield, fuelie meter body, air intake, and master cylinder top.

The interior can be best described as “rich.” Everything was trimmed in exterior matching candy apple red leather, with matching deep-pile carpeting. Special features included high-back bucket seats, brushed aluminum door panels with three sequential flashing reflectors on each panel, special gauges, brushed aluminum instrument and glovebox bezels, a red leather glovebox page with special “Stingray” script, red weatherstripping, and chrome floor grates.

When special cars, such as this, have fulfilled their mission, they are usually put into storage, sometimes sold, and occasionally destroyed. While in storage, the car was mildly vandalized and then repaired. A few years later the car was later purchased by GM executive Alex Mair as a gift for his 16-year-old son Steve. Mair had some minor upgrades and a functioning under-the-car exhaust system installed. Fortunately, Steve knew what he had, enjoyed the car, but treated it with kid gloves before he sold the car in the late ’80s. “Corvette Mike” became the next owner, followed by the owners of The Blackhawk Collection, and finally into Mike Yager’s collection. Yager had everything refreshed and made roadworthy, plus added an important feature. The non-functioning, plastic side-pipes were replicated and made into a functioning side-pipe system. In 2011, the car was valued at $1,250,000.

1965 Mako Shark II Concept

The 1965 Mako Shark II is arguably the most important concept/show car Corvette ever made. There are several factors to consider. First is the time context. The Sting Ray was already light years ahead of anything else on the road in 1964. The design has aged perfectly, such that even today, when you see a ’63-’67 Corvette on the road, it’s a head-turner. Even though the Sting Ray was a radical departure from the first-generation Corvette, Bill Mitchell, not content to rest on his laurels, wanted to take things even further. Little did he know that he would be creating the overall template that lives on today in the C7, as seen in the accentuated front fender humps that swoop down into the low grille. It is the signature Corvette “look.” There have been many interesting-looking concept cars that wore the Corvette badge, but didn’t look like a Vette. This “look” was so important that on October 25, 1966, Bill Mitchell received U.S. patent number 206,023 for design.

Mitchell could be a tough taskmaster, but he let his designers “design.” Here’s his vague instruction of what he wanted for the next Corvette, “a narrow, slim, ‘selfish’ center section and coupe body, a tapered tail, an all-of-a-piece blending of the upper and lower portions of the body through the center (avoiding the look of a roof added to a body), and prominent wheels with their protective fenders distinctly separate from the main body, yet grafted organically to it.” Got that? Clear as mud, right? Fortunately, Senior Designer Larry Shinoda had the unique ability of being able to see what Mitchell was vaguely looking for. The two men, along with Shinoda’s team collaborated until Mitchell’s inner vision was brought into reality.

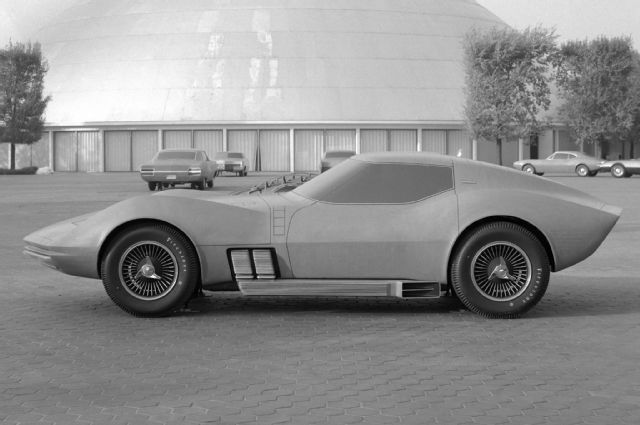

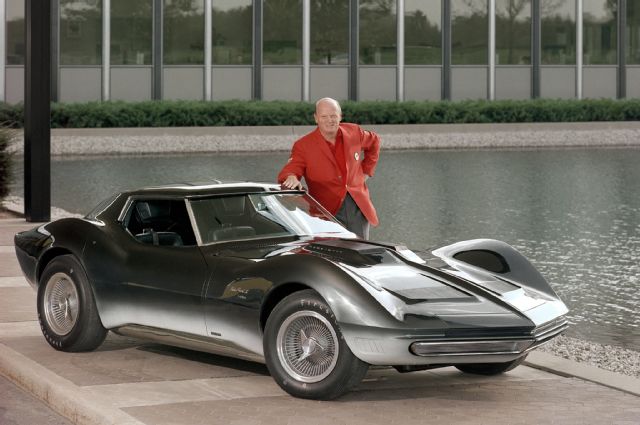

Once the shape was finalized, a fullsize, non-running, exterior/interior mock-up was created. Built on an existing production chassis, the mock-up was 3 inches lower than the already low-profile production Corvette and was deceivingly small. When the car was photographed in Styling’s viewing year with former Miss Teen USA, Conny van Dyke, the car looked much larger than it really is. However, there are other photos of Mitchell standing next to the Mako Shark II that clearly show that this is a tiny car—its proportions give the illusion of more size and mass than is actually there.

“Stunning” doesn’t quite describe the Mako Shark II compared to anything domestic or foreign in 1965. Mitchell loved sharp edges and lines because to him, it looked like a freshly pressed suit. The Mako Shark II is loaded with sharp lines and crisp surface changes. Yet, there are those sensuous, lusty fender hump curves, the pinched in “Coke-bottle” sides and Sting Ray coupe-like roof—but extra crispy. Even the front windshield was creased in the middle. Tire companies were just beginning to develop “wide” profile tires and the Mako Shark II was shod with Firestones, 8.80-inch on the front and 10.3-inch on the back—huge for the day. The aluminum wheels looked like the optional 15×6 knock-offs on steroids, measuring 15×7.5, thus providing a nice deep-dish look.

The interior of the mock-up was very futuristic. Most notable was the aircraft-style steering wheel with built-in controls. Production gauges were built into the dash that sloped down and away from the passengers. The raised center console was a “bundling board” of switches and controls. The seats were fixed and headrests were attached to the roof. The steering wheel and pedals were adjustable.

After the initial gush was over, it was time for the Mako Shark II to get to work. The first stop was the New York International Auto Show in April 1965 and the Mako Shark II was to be the belle of the ball, the star attraction in the Chevrolet booth. There was simply nothing like it at the show. Everything else was like Pat Boone trying to be the follow-up act to Elvis Presley. Meanwhile, back in the Chevrolet Design studio, the order was given to make a running version.

1965 Mako Shark II Prototype

The Chevrolet Design team had six months to build a fully functional show car in time for the opening of the Paris Automobile Salon Show on October 7, 1965. While the pressure was on to build a driveable Mako Shark II, there were battles going on inside Chevrolet as to which direction the ’67 Corvette should go. Pete Estes was the new general manager of Chevrolet and the Mako Shark II wasn’t yet a sure thing. Henry “Hank” Haga in Chevrolet Studio 2 presented a “next-Corvette” design in April 1964 that was very different from the Mako Shark, featuring mostly straight lines, a very long hood, and a cabin set way back. It was an interesting design, and would have made a very cool Pontiac, but didn’t scream “Corvette!”

When the Mako Shark was anointed as the “next Corvette,” product planners wanted it to be a ’67 model. Perhaps they thought that because the chassis, suspension, and drivetrain would all be carried over from the then-current production version, creating a new body and interior would be a snap. It turned out not to be the case and that’s another story. The new Shark Corvette was pushed back to a ’68 model that should have been a ’69.

The most noticeable difference between the mocked-up and running Mako Shark II is the absence of the side exhausts on the running prototype. The nose is very long and slopes down below the driver’s line of sight. Two large grilled air outlets towards the front of the hood helped vent hot air. Revolving headlights were at the leading edge of the nose. “Line of sight” was an issue with the car and many that drove it said that the large fender humps blocked more forward vision than they were used to. The windshield wipers were tucked away in a closet at the base of the windshield, a feature that made it into production.

Being 3 inches lower than the production Corvette, entering the car was difficult. The solution was the roof that lifted up from the back, interesting but not a real-world solution. Rearward vision had a Cadillac-sized blind spot because of the roof design. The rear window louvers were motorized and could be open or shut. The back end of the car had a retractable rear bumper and two retractable rear spoilers mounted at the rear leading edge of the duckbill spoiler. And finned, rectangular dual exhaust tips were under the rear bumper and in the center.

The interior was very futuristic and used fixed seats with an adjustable steering wheel and foot pedals. The dash was redesigned to include a neon counter-tube digital display and the center console had an array of switches and slide controls for heating and air conditioning. And attached to a conventional steering wheel and column were rotating thumbwheel controls. The accelerator and brake pedals were grated metal and quite large.

Making an awesome show car is one thing, designing a car for mass production is something else. There was very little unused space under the skin of the car. Seventeen fractional-horsepower motors, wiring, and fiber optic lines, in addition to the usual mechanical hardware, was all stuffed into a very small car.

The little teaser Corvette had no trouble working as a pace car at racing events, thanks to its 427 big-block engine and Turbo 400 transmission. As was often the case, Mitchell used the running Mako Shark II as a daily driver for a time. The running Mako Shark II had a short-lived period of stardom because once the ’68 model was released, the Shark’s once avant-garde status was exhausted. Unfortunately, this configuration of the Mako Shark II did not survive, but the car did. When the ’68 production version of the Shark came out, Mitchell pulled the show car beauty in for an overhaul. In 1969, the car was reborn as the Manta Ray and is still with us.