by Scott Parker as republished for SuperChevy

Built vs. Bought: Pitting Brian Hobaugh’s Pro Touring ’65 against a stock 2015 Z06

Dateline October 2015: Hot rodding is as American as apple pie. It embodies some of the most fundamental American concepts such as the ability to accomplish anything. An OEM can spend millions of dollars developing a car like the 2015 Corvette Z06, but we believe we can make it better. More over, we believe we can make a much older car even better than a brand-new car. Is it arrogant and even foolish? Probably, yeah… But this is the land of opportunity. And out on track, it doesn’t matter whether each part was meticulously designed by a separate engineer with FEA and CAD software, or grabbed from a rusty parts bin on a shop floor. Whoever crosses the finish line first wins.

Brian Hobaugh’s 1965 Corvette has been autocrossed pretty much since the day it left the dealership. Long before there were aftermarket chassis options with C4 and even C7 suspension, Brian and his father have been refining the handling of the mid-year one lap at a time. If you work with a particular platform or even just one car long enough, you really get to know each eccentricity and how to finely tune it for optimum performance. As such, it uses only a handful of well-chosen upgrades to the suspension, including Van Steel front upper control arms to get the right alignment, a Mike Maeier Inc front sway bar to control body roll (no rear bar), aftermarket stock-style springs, and JRi shocks all around. Borgeson power steering helps turn a massive set of Falken Azenis rubber measuring 315/30/18 at all four corners. As the GM of a body shop, Brian was able to massage the fenders to accommodate 18×12 Aristo Collection wheels. And of course, with the space afforded he upgraded the brakes using Wilwood six-piston front and four-piston rear calipers with 11.75-inch Spec-37 rotors. Last, but not least, a Lexan spoiler was installed to quell the mid-year’s notorious aerodynamic issues on track, and a Kirkey road race seat keeps Brian from sliding around the cabin amidst massive g-forces.

Though Brian’s ’65 Corvette certainly has a few modern enhancements, like forged wheels, big brakes, and sticky radial tires, it is at its core just a 1965 Corvette. And that is exactly what makes it such a great car to compare to a 2015 Corvette Z06. If it had an aftermarket chassis with C6 suspension and an LS9, then we’d just be comparing two forms of modern technology. Instead, we’ll be looking directly at Duntov’s original design versus seven generations worth of advancements to chassis development. The substantial tires and brakes on both cars should mostly cancel out, since the Z06 in question has the steel rotors as opposed to the high-dollar Z07 carbon package. However, electronics such as ABS, Magnetic Ride, and an electronic limited-slip differential are included in the C7’s many advancements. Love it or hate it, there is no denying that many of these sophisticated driving aids can make you faster (not to mention safer) on track. Meanwhile, computer-aided design has helped the engineers build hard parts even better like the C7’s aluminum frame that is 57 percent stiffer and 99 pounds lighter than the C6’s steel frame.

Instead of continuous hydroformed framerails with a constant 2mm wall thickness (like the C6), it uses five segments of aluminum with thickness varying from 2 to 11mm depending upon where stiffness is needed. This is also a stark contrast to the constant thickness, bent framerails of the C2 or even a quality aftermarket frame with 3mm mandrel formed, boxed steel frames. The C2’s perimeter frame, with its boxed steel rails, was thought to be a huge step up from the first generation. Yet the process of bending the frame into shape is notorious for producing weak spots, let alone what can happen over 50 years of use.

Beyond the actual construction of the chassis, the differences between the two generations are also vast. The layout is much different in that the C7 uses a transaxle as opposed to bolting the transmission directly to the engine. This, along with the use of many lightweight materials, helps the Z06 achieve a near 50/50 weight distribution of its 3,524 pounds. As many Corvettes enthusiasts know, though, the C2 had a rear weight bias. Many reported it to be 47/53 depending on which engine option, and weighed in about 300 pounds lighter than the C7. Hobaugh’s ’65 has been measured at 49/51 and 3,170 pounds. It is also smaller than the C7, 8-inches in terms of wheelbase and width but under 2-inches in length. All things being equal, Hobaugh’s ’65 should be more nimble and agile than a ’15 Z06.

In terms of suspension, all things are not equal and much credence should be given to the C7’s advancements. The C2 was crude by comparison, but, on the other hand, it was extremely effective. Unlike the C7, which uses transverse leaf springs in the front and rear, in true race car fashion the C2 came with front coil springs. The double wishbone setup that is now fully refined on the C7 (using composite to cut weight) was a massive leap forward for the C2 that helped rotate the car easily through turns. The C2’s trailing arm rear suspension, though, bares little resemblance to the double wishbone in the C7. Keeping control of the tail-happy big-block C2 race cars in the early days took a skilled driver and a good mechanic (even with the added rear antiroll bar).

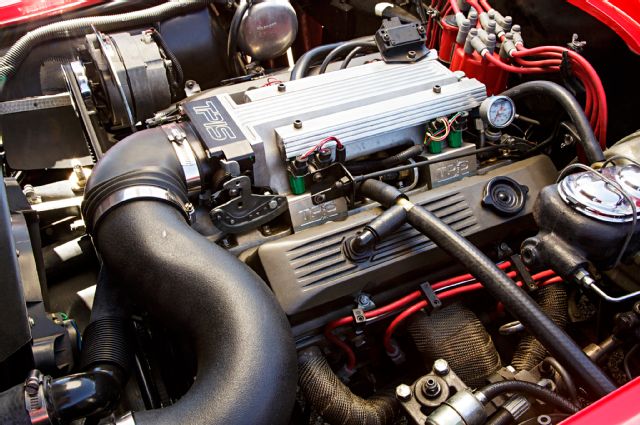

C7 Z06s are also known to be a bit happy, but for a much different reason. Oh, the mighty supercharged LT4. Sooner or later the subject of power would come up. The direct-injection 6.2L Gen V is an instant-on, fun-factory with 650 hp and 650 lb-ft of torque to light up the tires at will. Hobaugh’s ’65 has long since ditched its stock 327, and relies on a naturally aspirated 364-cubic-inch small-block to crank out 525 hp and 525 lb-ft of torque. Though it uses EFI and a nice set of aluminum 23-degree heads, the solid roller combination has less bottom-end and top-end than the LT4. On paper, the difference in horsepower will have keyboard jockies around the world crying fowl. But as we all know, all the power in the world won’t help you if you can’t use it.

Testing

Our friends at Super Chevy were gracious enough to loan us some track time during the Falken Tire 2015 Super Chevy Suspension & Handling Challenge at Willow Springs International Motorsports Park. The idea was simple: test a 2015 Corvette Z06 as delivered from Chevrolet against Brian Hobaugh’s 1965 Corvette on the autocross, skidpad, and slalom. We’d have Brian drive both as well as resident hotshoe and SCCA champ Mary Pozzi. Well, we had some logistical issues with the Z06 and it never made it to the autocross session on Day Two, but we learned quite a bit on the skidpad and slalom. If you aren’t familiar, a skidpad is basically just a large circle (200 feet in diameter in our case).

By pushing the car right to the edge of traction, and sometimes just beyond as it travels clockwise and counterclockwise, we can measure lateral acceleration, which is basically the car’s ability to grip the road. The slalom, on the other hand, takes steering and overall responsiveness into greater account. Our testing method included six cones set in a line, 70 feet apart for 420 feet total. With both tests we used timers, and then calculated the g-forces around the skidpad and average speed through the slalom.

Both the Falken RT615K (on the ’65) and the Michelin Pilot Super Sport (on the C7) proved capable of quite a bit of grip, aided by the balanced chassis design. Though our test driver remarked that it was difficult to not drift the Z06 around the skidpad, it averaged 1.013 g. Brian’s ’65, meanwhile, accomplished 0.97 g. The unevenness of the road may have exaggerated the difference between the two cars, favoring the C7’s stiffer chassis and on-the-fly valving changes by the Mag Ride shocks. The ’65 runs larger front tires and smaller rear tires than the C7, with what some would call a stickier compound. Doing some extremely crude math (adding up all the tire widths), it would appear that the ’65 has more rubber contacting the road than the C7 as well. But, the C7’s tires have an additional inch of diameter, which increases the contact patch. Without doing some extremely complicated measurements and calculations, we can’t say for sure which has the advantage in rubber, but it seems to be negligible.

The slalom was predictably where the much lighter and more nimble ’65 really shined. Brian averaged 49.3 mph on his best run, which was over 2 mph faster than the C7 Z06. Though the variable ratio electric steering of the C7 is an advantage over a fixed steering ratio, it simply gives up too much in size and weight. Plus the ’65 is also able to run a fairly aggressive static alignment, unlike the C7, which helps make the car that much more responsive. Alignment is often a very overlooked aspect when it comes to handling, but can drastically change the characteristics of a car. Of course, the suspension needs to be designed well enough to maintain that alignment under extreme loads. A soft bushing could cause erratic handling by deflecting or collapsing mid-turn, thereby going out of alignment.

Vehicle dynamics come into effect in many other ways on the slalom, too. Overall balance is key because if the car gets out of shape and is forced off its line, it will be impossible to turn in a respectable time. The car needs to be stiff – but not too stiff – and its body motion needs to be controlled and linear, so that it can easily be gathered up and pointed through the next cone. Poor weight balance; poor choice in springs, shocks, or sway bars can all play havoc on slalom times. And of course tire choice plays into this as well.

Conclusion

On a small, tight autocross course we give the advantage to Brian Hobaugh’s 1965 Corvette. It is the epitome of a well-sorted combination, refined through years and years of testing. Brian saw the genius in Duntov’s design and how to tune it to his advantage using a few modern advancements, but mostly just hard work. The difference in power is not a factor on tight courses with a max speed of 50-60 mph, and the beastly LT4 could even be a nuisance when trying to apply throttle coming out of a turn.

On a large track with uneven surfaces like Sebring, Road Atlanta, or Laguna Seca, the 2015 Corvette Z06 is hard to beat. It’s power alone gives it an advantage on large straightaways, but the added grip would help it pull away on long, sweeping turns as well like turns #1 and 17 at Sebring. It was those very turns that C7.R drivers noted how much more stable it is than even the C6.R, thanks its new chassis. Of course, the supercharged Z06 may have some heat-soak issues when running some of these longer tracks, whereas the C2’s naturally aspirated small-block is built to run all day and take whatever abuse Brian can dish out (not unlike the C7.R).

Whether you like the classics or late-models, it is safe to say that they all have tradeoffs. There is no clear winner in our debate over built versus bought. But what we can conclude is that pretty much every car can be improved upon – even an $80,000 supercar. And in doing so, we can leave the soul of the car intact while vastly improving its performance and having a great time doing it. Of course, if you want to take it even further than that, the Vette staff won’t object.

Sources

Falken Tire

Fontana, CA 92335

800-723-2553

http://www.falkentire.com