A look back at Chevrolet’s experimental, prototype, concept car, and show car Corvettes

Art & Words by Scott Teeters as republished from Vette Magazines SuperChevy.com website. Part 1, Part 2, Part 3

General Motors makes hundreds of kinds of cars and trucks. Some sell hundreds of thousands of units a year, which makes Chevrolet’s Corvette a complete enigma. Given the small number of Corvettes sold every year, it is a modern American manufacturing miracle that the car survived for 61 years.

The Corvette was “officially” born on January 17, 1953 at the GM Motorama Show at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel, in New York. To understand the impact of Harley Earl’s two-seater sports car concept car, you have to look at typical cars of 1953. The car was low and sleek, and wasn’t over festooned with styling gimmicks. Based on the response from attendees, Chevrolet rushed the car into production, and the rest is history.

Today, the Corvette is GM’s flagship car. When Chevrolet unleashes a new Corvette, the automotive world stops to take notice. But things were not always this way. Up to the C4, there were many inside GM that wanted to see the Corvette go away. For the first 20-some years, the car suffered from an identity crisis. Inside GM there were always those that wanted the Corvette to be something different; a lightweight sports car, a mid-engine car, a rear-engine car, a four-seater personal luxury car, powered by a boxer-type flat-six, Wankel rotary-powered, turbocharged small-displacement hemi-headed double-overhead cam powered, and even an all-aluminum car. Chevrolet kept the loyal faithful stoked with two or three experimental, prototype, show car Corvettes per year. From an enthusiast’s perspective, this was endlessly fascinating.

This is part four of a chronological look back at Chevrolet’s high-profile experimental, prototype, concept car, and show car Corvettes. Some of the cars had exotic names such as, “Astro-I,” “Astrovette” and “Geneve.” Others had experimental prototype numbers, such as “XP-700” and “XP-882.” And some had sexy names, such as, “Nomad,” “Mulsanne,” “Snake Skinner,” “Mako Shark,“ and “Tiger Shark.” In retrospect, a few of the cars were the shape of things to come, but most were simply, “Here’s an idea of something we’re working on.” Either way, it was all a ton of fun!

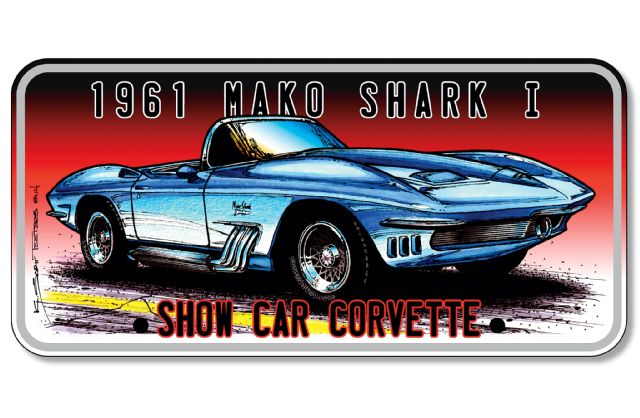

1961 Mako Shark I

What looked like a prototype Corvette was in actuality another in a long line of teaser show cars. After nine seasons, Corvette lovers were ready for a new machine. The XP-755, called the “Mako Shark,” was truly the shape of the future. What Corvette fans didn’t know was that while the Mako Shark was knocking their socks off, Chevrolet was hard at work sorting out the final design of the ’63 Corvette. This was no small task, as everything except for the engine, transmission, and brakes was completely new. Except for details such as vent placement, grille, and bumper shapes, the second-generation Corvette was nailed down.

Meanwhile, Zora Arkus-Duntov was having a field day making an all-new, advanced chassis for the new Corvette. Outside consultants Jerry Titus, John Fitch, and Karl Ludvigsen were given the opportunity to drive a prototype for their evaluation. Zora and Bill Mitchell had a volcanic argument over the new Sting Ray’s rear “split-window” design. Mitchell was offended that a lowly engineer on a low-volume Chevy line would dare to tell him how to style his pet car. According to Larry Shinoda, the fur really flew! Zora called Mitchell a “red-faced baboon” and Bill called Zora a “White Russian.” Consequently, Mitchell was not invited to drive Duntov’s latest chassis prototype! So, Bill built an exaggerated version of the XP-720 as a show/personal car.

Officially, Mitchell felt that the automotive press was getting too close to the real Sting Ray (the Stingray Racer was a BIG hint), so a radical show car version was needed to “throw off the scent.” While lead stylist Larry Shinoda was in charge of the styling details, when designers asked Mitchell, “How far should we go?” Bill answered, “Keep going it until I say ouch!” Shinoda stretched the nose 12 inches from what would be the real Sting Ray and the headlights were recessed well below the legal height limit. The name and the iridescent blue to white paint design mimicked an actual mako shark that Mitchell caught while on vacation in Bimini.

Since its debut at Elkhart Lake and then the official unveiling at the New York Auto Show in April 1962, the Mako Shark had gone through numerous detail and hardware changes, yet still looked essentially the same. Built on a ’61 Corvette chassis, the XP-755 shape was “close” to the developing ’63 model. The fender humps were exaggerated and surface add-ons decorated the car almost to the point of overkill, but hey, it was supposed to be a show car. The Plexiglas, bubbletop, and prismatic periscope were carryovers from Mitchell’s XP-700 dream car.

Originally, the Mako Shark had a stock ’61 Corvette interior, except for tight bucket seats and a Ferrari steering wheel that was gift from Enzo Ferrari. The engine was a 327 with a small, Roots-type supercharger and four side-draft carburetors. Outrageous four-pipe side-pipes exited from each front fender. Chromed Dayton knock-off wire wheels gave the car that European look. Years later, the interior was redesigned with flat panels and gauges, a 427 engine with an automatic transmission was installed, and alloy lace wheels with wide ties were used.

As per Mitchell’s command that show cars be functional cars, the Mako Shark was a beast—just the way Bill liked them. The Mako Shark looked like a street version of the ’59 Stingray Racer. For a time, the Mako Shark, as well as the Stingray Racer were Mitchell’s daily rides. It was good to be the VP of Design. Corvette fans were more than ready for the real thing, but had to wait 18 months.

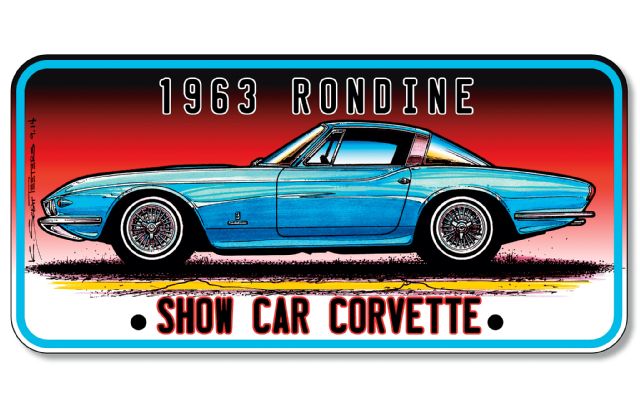

1963 Pininfarina Rondine

Have you ever noticed the similarity between exotic Italian cars and Corvettes? Many have and there’s a clear reason. Harley Earl and Bill Mitchell were quintessential “designers.” They lived in a world and at a time of beautiful design. Italian design was always about passion and lust. That’s why their cars tended to be curvaceous and sometimes busty.

While attending the 1957 Turin Auto Show, Bill Mitchell was the heir apparent to the throne of GM Design. Working at the side of Harley Earl, Mitchell knew everyone who was anyone in design. Mitchell was very impressed and inspired with Battista “Pinin” Farina’s Abarth 750 Bialbero land speed record car. Mitchell staged an in-house competition among his designers with the Pininfarina speed machine as their inspiration. Designers Peter Brock and Chuck Pohlman’s sketches won the competition. From there Pohlman and Larry Shinoda made a full-size model to make molds from, and the Stingray Racer was born. This was the car that launched the “Shark-look.” So, you could say that Battista “Pinin” Farina is a first cousin of the classic Corvette shark look.

Bill and Battista had an established professional and personal friendship as “car guys” and “designers,” and Pininfarina was in the exotic coach building business, designing and manufactured cars for Ferrari, Alfa Romero, Lancia, and others. When the new ’63 Sting Ray was released, Mitchell thanked his friend by sending him a ’63 Sting Ray roadster with a 327/360hp fuelie and a four-speed transmission. The basic instruction was, “Re-body any way they wish.”

Pininfarina charged American designer Tom Tjaarda with the task of designing an edgy car using the Corvette’s basic structure. While Ferraris were famous for their voluptuous curves, there was a new move in European design that was more linear, with sharp creases; something Mitchell loved because to him, it looked like a freshly pressed suit. Designer Tom Tjaarda later went on to design the Ferrari 330 2+2, the Fiat 124, and the De Tomaso Pantera.

The name “Rondine” is Italian for “swallow” after the design’s “pinched in” rear treatment. Made in steel, the Rondine’s definitive side crease that kicks up at the back of the doors, then slopes down to the back and then forms the “pinched swallow look,” was later used on the Fiat 124 Sport Spider. By extending the sharp horizontal beltline farther towards the front, it gave the look of having the interior farther back. Dual headlights were semi-hidden and mounted behind Plexi covers, with a small top door that opened when the headlights were turned on. The front bumpers were styled very much like the Sting Rays but were longer with a more radical back sweep on the lower part of the bumpers. The center grille section had horizontal ribs with two vertical dividers. The design looked a little like the ’61-’63 Thunderbird—sort of.

As shown originally in 1963, the rear glass stopped just behind the B-pillar, then dropped down, like the ’63 Mercury Monterey. The second and current configuration is a graceful, all-glass, wraparound semi-fastback. This design opened up the otherwise very small rear compartment area and brightened up the stock, white leather-trimmed upholstery. Extra details were added to the lower edges of the door panels and the doorjambs were chrome.

Painted metallic turquoise, the Rondine made its debut at the Paris Salon Auto Show in October 1963. Pininfarina was hoping to generate some custom coach-building business with the Rondine. It didn’t work out. Although the Rondine is a beauty in its own right, it just didn’t set anyone on fire with desire. After making the rounds in the car magazines, the Rondine became a permanent part of the Pininfarina Museum until 2008 when it was sold at the Barrett-Jackson Scottsdale auction for $1.6 million. A private collector in Connecticut now owns the Rondine.

1963 Grand Sport Corvette

The 1963 Grand Sport is arguably the greatest “could’a been” Corvette. For this series, we’ll look at the Grand Sport from inception to the International Bahamas Speed Week event in Nassau, in December 1963.

Beginning in 1957, Duntov made sure that would-be racers could buy well-engineered parts for their Corvettes. As the new ’63 Corvette worked its way into production, Duntov developed a new option to take advantage of the new suspension and layout. RPO Z06 cost a whopping $1,818, plus $430 for the 327 fuelie engine. This should have been enough, but Duntov wanted more. Four months before the debut of the Cobra, Duntov convinced Chevrolet general manager Semon Knudsen that an ultra-lightweight, factory-produced Corvette was necessary. In June 1962 Knudsen approved Duntov’s plan to build 125 “lightweights”: 25 for Chevrolet and 100 for privateers. Construction began in July 1962 and the first “Grand Sport” was completed in November 1962.

However, trouble was spotted at the Los Angeles Grand Prix in October 1962, when the new Z06 and the Cobra made their debut. Four Z06s were entered, one finished, and won the race, ONLY because the leading Cobra broke an axle hub, allowing Mickey Thompson’s Z06 to take First place. Two months later, Duntov took the first Grand Sport to Sebring for testing and was only seconds off the track record. Things were looking bright until GM chairman Frederick Donner reiterated the official “we do not race” edict, thus killing the Grand Sport. Five Grand Sports had been produced and while Chevrolet wasn’t allowed to race them, three Grand Sports were loaned out to favored racers, but were starved for support. The first win didn’t happen until August 1963 at Watkins Glen for Grand Sport #004 with Dr. Dick Thompson driving. In October, with the season over, Duntov had the three raced Grand Sports returned for “improvements” for the upcoming International Bahamas Speed Week event in Nassau.

The Grand Sport had a steel tube ladder-type chassis and lightweight suspension, but the car looked almost like a stock ’63 Corvette. All-aluminum experimental 377 small-block engines with a special cross-ram fuel-injection system were installed for extra grunt, making the entire engine and drivetrain lightweight aluminum. With 485 horsepower on tap, the Grand Sport needed bigger tires. The original 15×6 Halibrand wheels were replaced with 15×9.5 wheels in the front and 15×11 wheels in the rear, shod with the latest Goodyear Stock Car Special tires. To cover the big tire/wheel setup, a muscular set of fender flares were grafted to the body and a tall, wide domed-hood with two forward-facing scoops helped feed the aluminum engine. Lastly, the fake front fender vents were made functional and across the back, eight vent holds were added between the brake lights to release heat and trapped air. Finally, the Grand Sport looked MEAN

There were three Nassau races, the December 1, 99-Mile Tourist Trophy Race, the December 6, 112-Mile Governor’s Trophy Race, and the December 8, 252-mile Nassau Trophy Race. During the Tourist Race, overheating differentials forced the two entered Grand Sports to drop out. The solution was to install a small radiator on the rear deck, just behind the rear window. The fix worked and in the 112-Mile Governor’s Trophy Race, the three Grand Sports took First, Second, and Third place in the prototype class! A Cobra came in Eighth. For the December 8 Nassau Trophy Race, the Grand Sports took First and Third in the prototype class with a Cobra coming in Seventh.

The Grand Sports simply out-powered the 289 Cobras. Duntov, Knudsen, and the entire team set their sites on Daytona and Sebring. The two remaining Grand Sports were to be converted into roadsters. Duntov had Le Mans in mind. But everything came to a halt in January 1964 when Donner threatened Knudsen’s yearly bonus. Money talks and the Grand Sport adventure was finished. The cars were loaned out and eventually sold to privateers but the Grand Sport did have minimal success.